Frankfurt’s Masters of the Sword and Their Lost Emblem 🛡️ Part III

The Marxbrüder 1670 armorial augmentation was never lost. It was simply waiting for someone to look in the right place. After a year of searching across Frankfurt, Basel, and Vienna – and after confidently assuming the charter had perished – I finally found it in the last place I expected: a velvet-bound booklet in a special box, surviving the centuries despite forced openings, fire, relocations, and archival reshuffling. And it had been here in Frankfurt all along.

This article presents the first full analysis of this remarkable heraldic achievement.

Although I do not claim to be the first to have rediscovered it1 – nor the first to have overlooked it (it is rather well-hidden) – I hope the following contributions help to compensate for this oversight:2

- The first extensive analysis of the piece, including a full transcription

- Assistance in preserving and making it publicly available: Similar to the Basel charter of 1541, I requested a high-resolution reproduction which should be openly accessible in the following weeks3

- An updated, high-fidelity vector representation, freely usable by anyone

- A reconstruction of the charter’s and the entire holding’s archival history

For those interested in the history of the charter (and how it managed to elude me), more on that appears toward the end of this article. For now, let’s turn to the document itself.

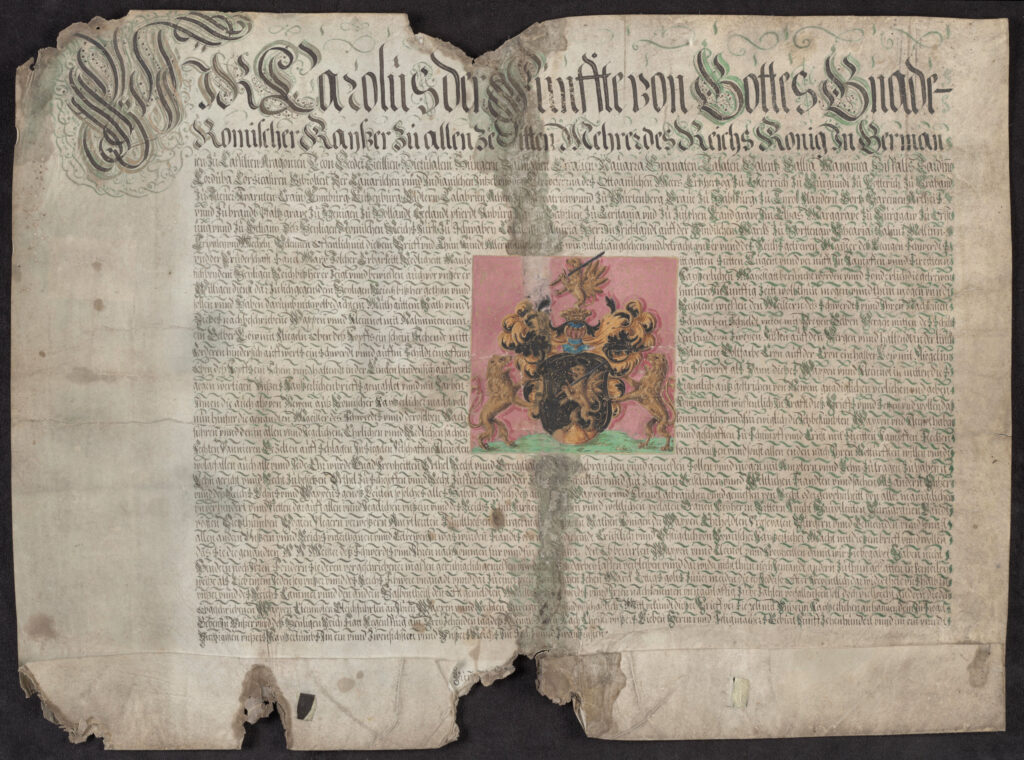

The Resurfaced 1670 Armorial Augmentation of the Marxbrüder

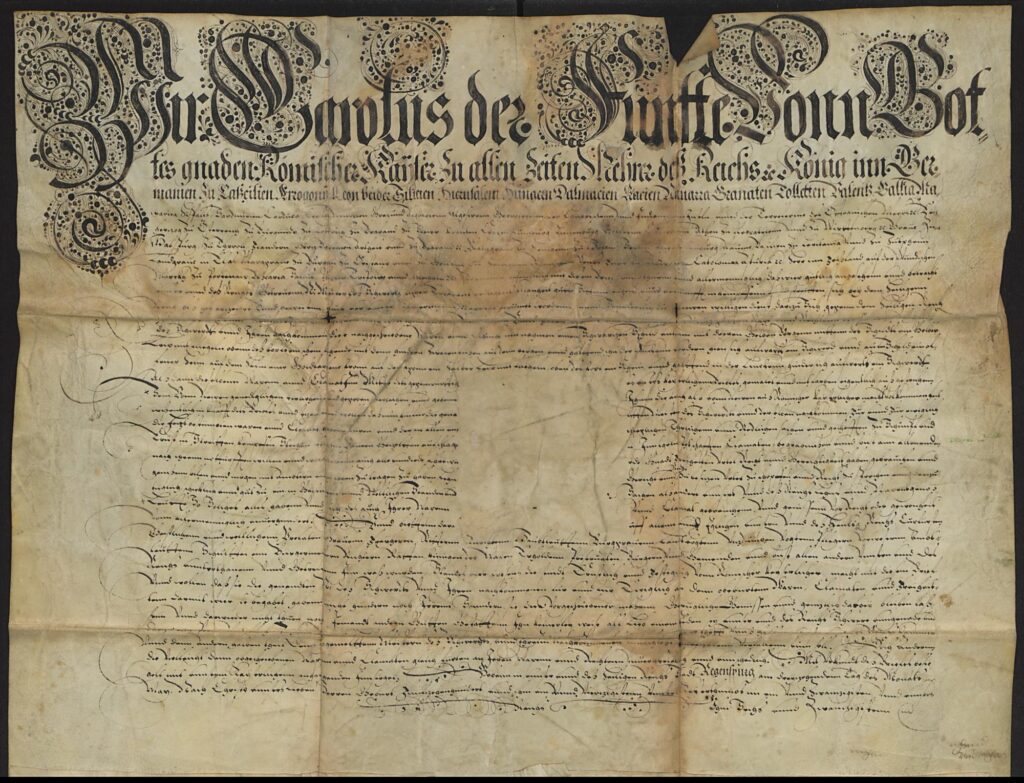

The long arc of this inquiry finally bent home. In the quiet, expectant days of the winter holidays, I found out that the armorial augmentation by Leopold I was, in fact, not lost; it had been resting here in Frankfurt all along, tucked away in a special box under signature ISG FFM H.18.03 Nr. 32.4

Naturally, my curiosity about this original charter – and the precise rendering of the coat of arms within – demanded a closer look. As soon as the archive reopened for the new year, I requested access, eager to see how the physical document compared to its reputation.5

First Encounter with the Charter

Ordering manuscripts is always a bit like playing archival roulette — you never quite know what will slide across the counter. This time, instead of the plain A3 envelope typical of many Marxbrüder charters, I was handed a large, flat grey box. It was the sort that immediately tells you you’re in for a surprise.

Opening it with due caution, I found a booklet, roughly A4 in size, bound in regal crimson velvet and fitted with yellow ribbons. While they were unfastened when receiving the piece, I successfully managed to resist the intrusive thought of neatly tying them into bows for the photograph below. Until the high-resolution images arrive, we must make do with my own hasty pictures.

Most striking of all, attached to a gleaming golden thread running down its spine was a curious, UFO-shaped wooden object with delicately smoothed edges and flaking red-gold paint – something like an oversized Baroque yo-yo.

Only after taking in its staggering diameter of roughly 25 centimeters did I realize that this circular wooden box was the skippet protecting Leopold I’s grand Imperial seal (which truly lives up to its name) from melting or cracking.

The Grand Imperial Seal: Iconography and Structure

Opening the lid indeed revealed an ornate red wax seal within a more austere yellow socket. The skippet had not entirely succeeded in protecting it: the seal shows a visible crack toward the lower right and a melted spot at three o’ clock, perhaps incurred by careless handling.

Upon it, two griffons proudly present a U-shaped Iberian shield set within a decorative cartouche – a style particularly fashionable during the Baroque and Rococo (c. 1600–1750), and squarely the period to which this charter belongs.

On the shield appears the haloed double eagle of the Holy Roman Empire with excitedly protruding tongues and on sharp lookout to the left and right. Its chest is adorned with a small heart-shield bearing the arms of Austria and Castile. Presiding over the entire ensemble is the Imperial crown of Leopold I, whose inserted mitre uncannily resembles a well-risen loaf of bread topped with a pious cross.

The shield is embraced by the chain of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Eleven smaller shields representing the kingdoms (e.g., Germany at the center, Bohemia, Hungary) and hereditary lands (e.g., Styria, Carinthia) are neatly arranged around the outer ring. Surrounding them runs a circular inscription with Leopold’s Latin intitulatio:6

Leopoldus · Dei · Gratia · Electus · Romanorum · Imperator · Imper · Augustus · Germaniæ · Hunagariæ · Bohemiæ · Coratiæ · Schlavoniæ · zc · Rex · Archidux · Austriæ · Dux · Burgundiæ · Stiriæ · Carinthiæ · Carniolæ · et · Wirtembergiæ · zc · Comtes · Tyrolis · zc ·

Inside the Velvet Volume: Script, Layout, and Contents

Still captivated by the seal’s grandeur, I turned to the velvet-bound volume itself. Inside, ten parchment folios formed the gatherings that contained the Marxbrüder armorial augmentation granted by Leopold. Apparently, the privilege incurred water damage during storage as all pages toward the binding exhibit a pronounced, irregular water stain with dark brown discoloration and marginal foxing.

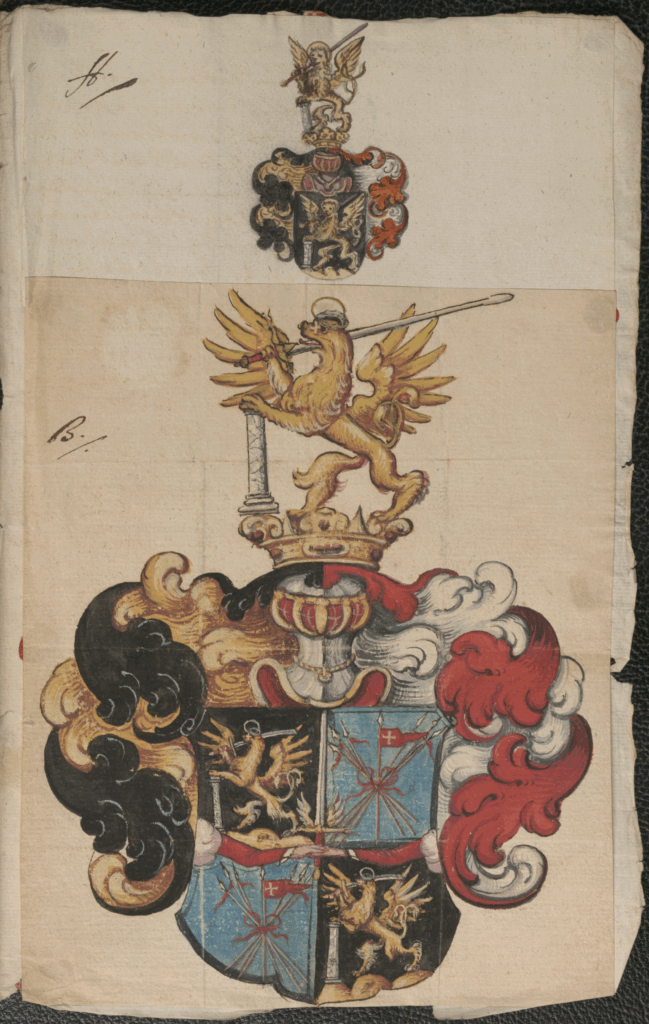

Set in ornate chancery script, the opening lines “Wir Leopold von Gottes gnaden Erwöhlter […]”7 were already familiar to me from the Viennese concept of the Aulic Council,8 which I had studied closely for my earlier heraldic reconstruction.

The remaining text is executed in a fluent chancery Bastarda, with the exception of folios 2v to 5v. These contain a copy of Charles V’s 1541 armorial grant – previously discussed in my first article9 – penned in a somewhat hurried Kurrent script.

As was customary for imperial privileges of this era, the charter is authenticated by the faded, double-underlined signature of Emperor Leopold I himself, accompanied by the more orderly signature of Imperial Vice-Chancellor Leopold Wilhelm Graf von Königsegg.10

Recorded within the text is the specific petition of the “Masters of the Long Sword and Experienced Practitioners of Military Exercises of St. Marco and Löwenberg” to renew their old privilege, while also requesting that the Emperor increase their standing.11 In response to this “reasonable request,” Leopold granted the augmentation by citing their “honor, honesty, manliness, good morals, virtue, and reason in fighting, battling, and jousting” (normal stuff).12

This decree ensured that the Marxbrüder arms were not merely confirmed but – in the legal phrasing of the Aulic Council – officially vermehrt, geziert und verbessert (“augmented, adorned, and improved”).13 This improvement set the stage for the more elaborate heraldic display that followed.

Battle Swords and Marble Pillars: The Blazon of the 1670 Arms

Immediately preceding and surrounding the illuminated arms, the charter provides their formal heraldic description. This blazon, found on fol. 6r to 7v, serves as the legally binding definition to which any reproduction must adhere. In terms of content, the text offered no major surprises, matching the Viennese concept word for word.14 Nevertheless, encountering this authoritative version in such an artfully rendered form lent the description a weight and permanence that no working copy could replicate.

I provide my translation of the blazon below – and if you are eager to look at the painted arms already, please feel free to skip ahead to the next section. For everyone else: take a deep breath. As befits a Baroque armorial augmentation granted by the Holy Roman Emperor, the description is generous in its heraldic detail, spanning two folios or four pages. It may have been for the best that the Marxbrüder received only one such augmentation.

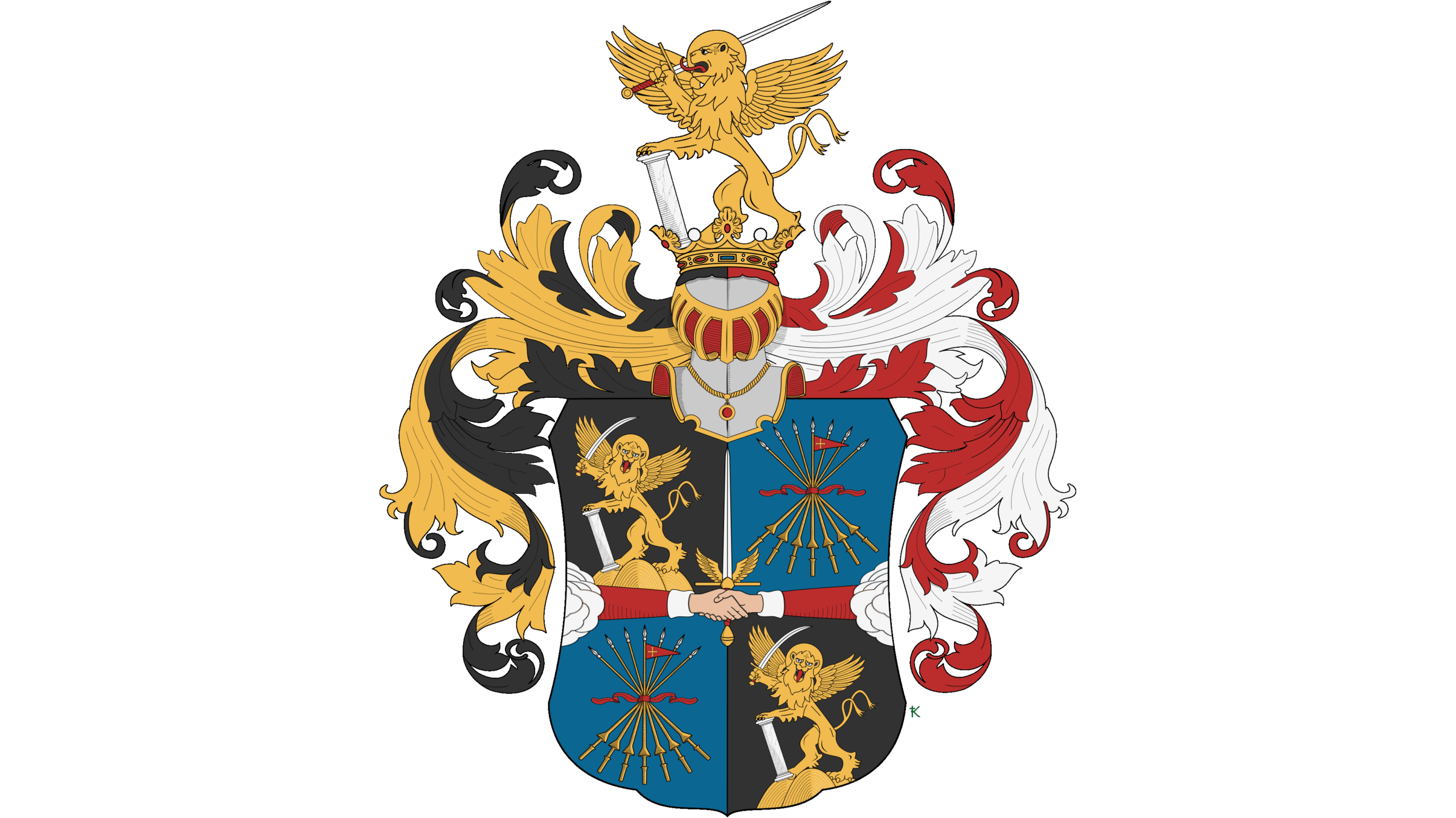

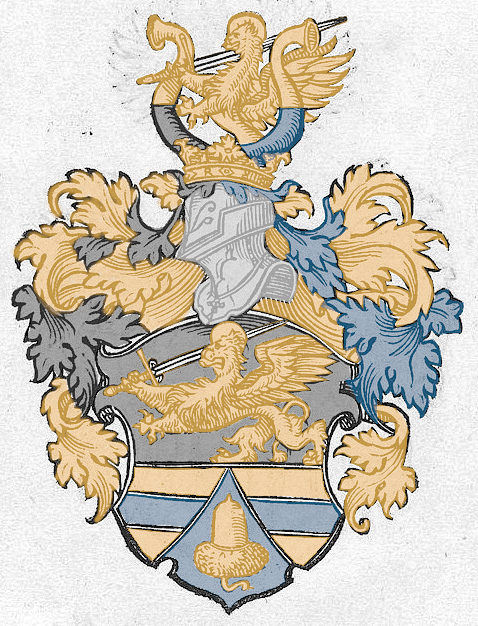

A quartered shield, whose first and fourth field15 is black with three golden mountains at the base. On these appears, facing forward, a golden16 winged lion, with his tongue out, wings spread, and a double tail. A cross is marked on his forehead, a green laurel wreath crowns his head, and above his head appears a golden halo. He stands with his hind paws upon the two rear mountains, holding in his left forepaw a white-striped marble pillar resting on the third mountain. In his right forepaw he raises a saber with a gilded crossguard and pommel, behind himself and upward as if ready for battle.

The second and third field17 is sky-blue mixed with ruby.18 Therein appear six jousting lances arranged crosswise with their points upward, three to the right and three to the left. At their center stands an upright pike19 bearing a tapered blood-red pennon marked with a golden cross. All are held together in the middle with a red band whose ends fly downward.

At the center of the shield appear two men’s arms clad in red with white cuffs reaching toward each other, emerging from clouds on both sides. They hold together a battle sword with a red grip, gilded crossguard and pommel, its point rising toward the open tournament helmet. Instead of the Schilt, the sword bears golden eagle wings with outward turned bases.

Above the shield rests an open noble tournament helmet, to the left with red and white, to the right with golden and black mantling,20 and above adorned with a golden royal crown.

Upon it appears the entirely golden winged lion with his tongue out, wings spread, a double tail, and a golden cross on his forehead, crowned with a green laurel wreath, and a golden halo above his head. He stands with his hind paws on the crown, holding in his left forepaw a white-striped marble column resting on the crown, and in his right forepaw a bare battle sword21 with gilded crossguard and pommel and a blood-red grip, raised behind himself for battle.

As exhaustive as this description is, the written word can only capture so much of an armorial grant. While the Aulic Council was still polishing the final phrasing, an armorial painter was at work translating those instructions into a piece of art.

The question remains: how faithfully did the brush follow the pen? To find out, let us take a close look at the physical painting and its iconography – contextualizing it with the later copies, the Viennese concept, and my own humble attempt at reconstruction.

The Painted Arms: Artistic Choices and Heraldic Details

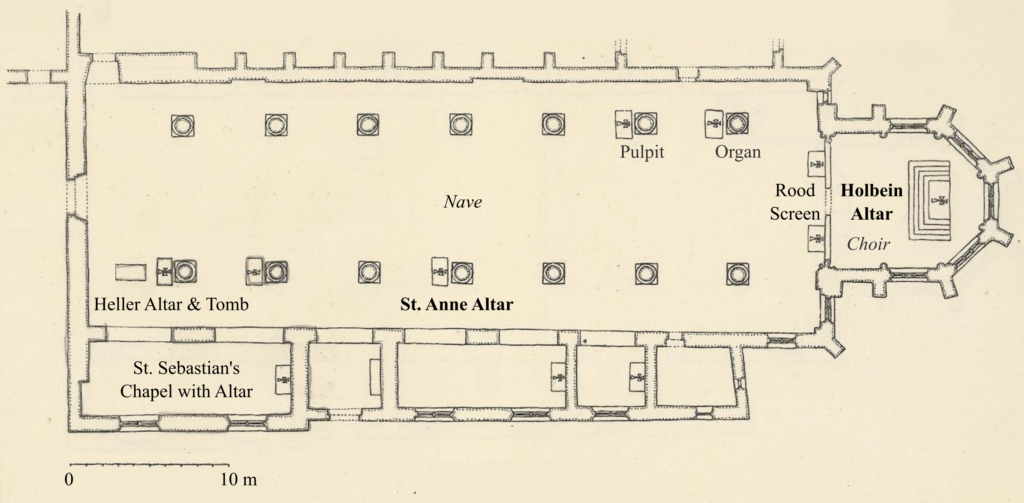

The centerpiece of the privilege – the full-color depiction of the augmented coat of arms – is set within an ornate golden frame on folio 7 recto. Upon first viewing, it becomes clear that the armorial painter took certain liberties with the 1670 blazon. In doing so, he pays direct homage to the composition of Charles V’s original grant of 1541.

Architectural Frame and Allegorical Figures

The arms themselves are set against a picturesque landscape (perhaps Austrian or otherwise Alpine) featuring lush bushes, a calm lake, and distant mountains, all viewed through a Roman-style, pillared doorway. The structure is surmounted by a golden emblem bearing the Imperial double eagle, topped with the mitre crown that we already encountered on the seal.

Flanking the doorway stand two classical figures in golden armor and with plumed helmets: On the left appears Mars, god of violent war, armed with an impractically small saber – hardly suited to this vocation – and a more respectable blue shield, handsomely embellished. On the right stands Minerva, goddess of strategic war, holding a spear tipped with a black pennon.

The Heart of the Achievement: The Shield

With this theatrical frame established, the eye is drawn to the quartered Iberian-style shield standing on an ornately carved stone pedestal at the center:

Quarters 1 and 4: Display the golden lion of St. Mark on a black field. The artist appears to have taken the minor liberty of arming him with a sidesword rather than the prescribed saber, somewhat mirroring the 1541 grant and establishing a dichotomy with the two-handed “battle swords” at center and crest.

Quarters 2 and 3: These originally showed a bundle of golden jousting lances with a red pennon on a blue ground, but have unfortunately suffered significant water damage. Given the blazon and my previous reconstructive work, however, we know with some certainty what they looked like – I provide a high-fidelity depiction in the following section.

Center: From clouds to either side emerge two arms in red sleeves with white cuffs, lifting a golden-winged long sword with a red grip and gilded pommel and cross.

Crest: The winged lion of St. Mark reappears above the noble helmet and its relatively austere crest coronet. Although both this lion and the ones on the shield ought to be depicted with “wings spread,” this one has his to the right thereby mirroring the 1541 grant. He looks slightly upward to the left with a strained grimace – as though he had struck his hindpaw against the massive marble pillar he is obliged to carry. I was admittedly surprised to see the lion still wearing a green laurel wreath.22 I had assumed a head already adorned with both a golden cross and a golden halo would have been deemed sufficient by the Aulic Council’s final reviewer23 – but I stand corrected.

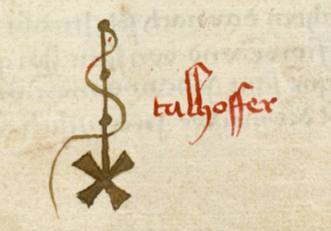

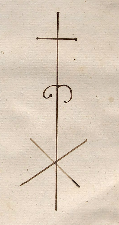

Symbolism of the Pillar: All three lions bear a white marble pillar under their left forepaw. I interpret this as an homage to Emperor Charles V,24 Leopold’s “cousin and ancestor resting in God”25 and patron of the 1541 armorial grant that is hereby augmented. Charles’ personal emblem consisted of the Pillars of Hercules with the motto PLVS VLTRA (“further beyond”), symbolizing the expansion of his realm beyond the Strait of Gibraltar into the New World.26

Together with the Roman-style framing, the marble pillar also evokes the Translatio Imperii – the transfer of the Imperial mandate from ancient Rome to the Holy Roman Emperor – underscoring the brotherhood’s position as an imperially privileged body and situating it within the ideological lineage of Roma Aeterna. Beyond these associations, the pillar remains a classic emblem of constantia (steadfastness).

Mantling: Flowing from the helmet is an opulent acanthus-leaf mantling: black and gold to the left; red and silver to the right.

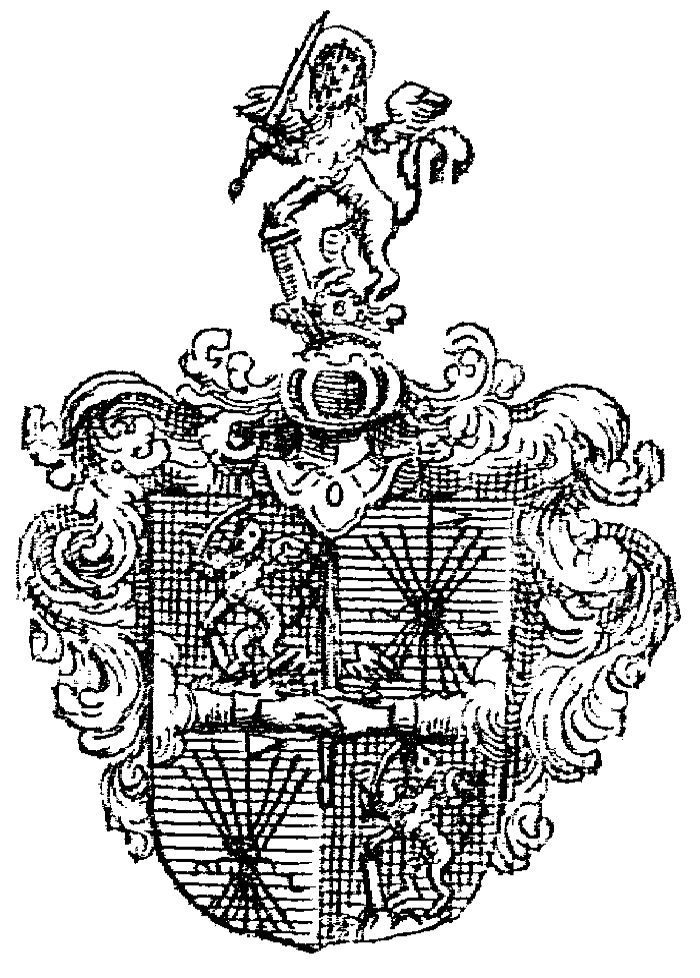

I also note that the original colored depiction closely mirrors the later monochrome copy we already encountered in prior articles (which is featured on Wikipedia). Therefore, it is likely that the copyist had access to this original armorial charter. Except for the lack of tincture and resolution, differences appear minor.

Updated Vector Representation of These Marxbrüder Arms (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Below is my updated colored vector representation of these arms, now fully aligned with this 1670 source. The few artistic deviations carry no heraldic significance – for instance, the shield shape follows the Viennese concept more closely, and the mantling adopts a slightly different stylistic flourish.

Notably, the lions in fields 1 and 4 continue to wield sabers with a slight curvature. Although the 1670 armorial painter appears to have chosen straight single-handed arms (perhaps sideswords) for his illumination, this is compliant with the legally binding blazon. This choice also ensures greater visual continuity with the later Kaehl print.

While I do not possess Imperial authority, I can at least grant you free usage of these arms under a CC-BY SA 4.0 license. Sources for all vector assets can be found in the Appendix.

A Charter Lost and Found: Tracing the Archival Journey

Before I conclude, it’s worth appreciating the eventful history of this piece – because the story of how it resurfaced is almost as fascinating as the charter itself.

Why the Charter Seemed Lost

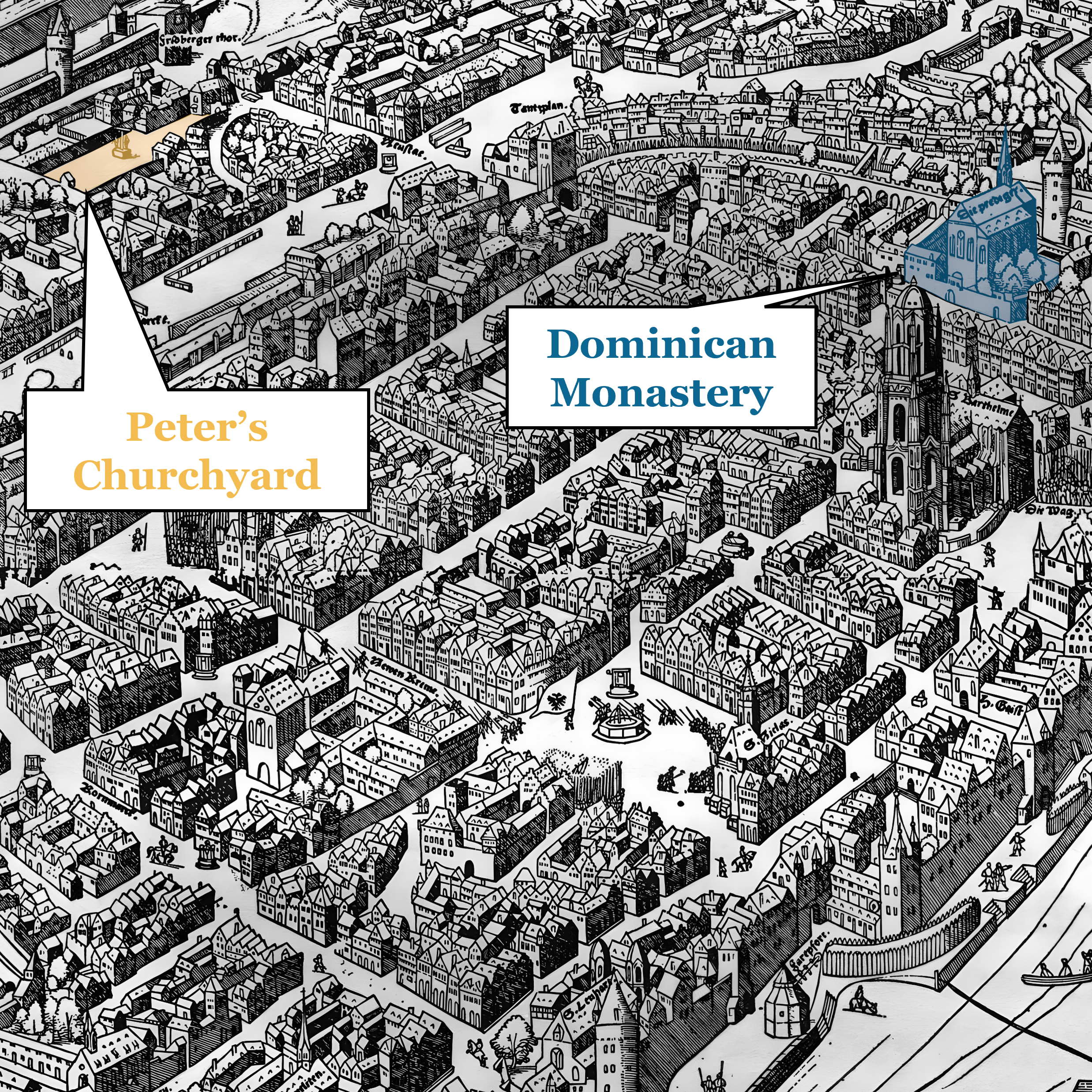

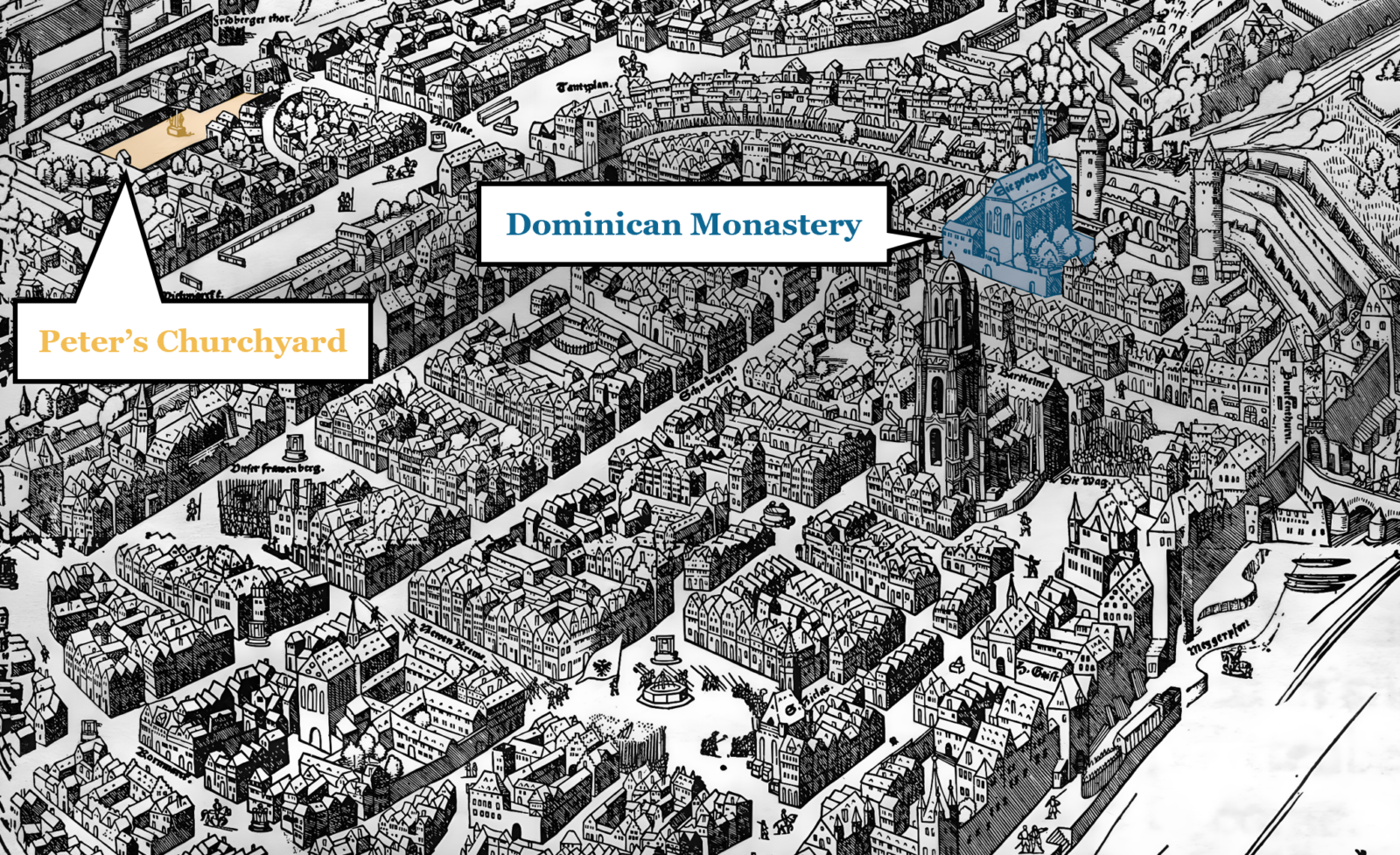

The Marxbrüder holdings are not yet digitally catalogued. The archive information system only reveals that there is a total of 64 documents (or 1 m of shelf space), spread among two archival collections with no openly accessible table of contents or internal structure. Earlier scholarship began digitally cataloguing (and transcribing) the first collection (H.18.12) with the charters and records of Frankfurt’s city council.28

The better-researched first half of documents contains every Imperial privilege except the 1541 armorial grant and the 1670 augmentation. This absence initially fueled my suspicion that they had been lost – perhaps in the fires of World War II29 or by other means. When I consulted a colleague about their whereabouts, they confirmed this: to the best of their knowledge, Frankfurt no longer held those specific letters.30

I only arrived at the truth much later, when I examined in detail how the second collection (H.18.03) entered the archive’s holdings. These 32 documents (formerly 55) had been kept separately by the Marxbrüder in their iron guild chest, alongside the brotherhood’s treasury, formerly liturgical objects,31 and fencing weapons.

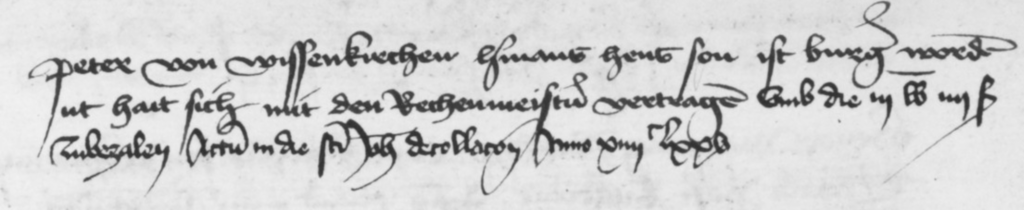

A council protocol from 3 April 1703 reveals that councilman Johann Lorenz Hangmantel had obtained these holdings from the Marxbruder and baker Johann Conrad Hartmann,32 whom the brotherhood’s records identify as a master in 1686.33

Unsealing the Past: The Baker and the Iron Chest

After vanishing from the records for several decades, the holdings resurface on 10 January 1788 in the possession of Johann Georg Motz, a master baker and councilman.34

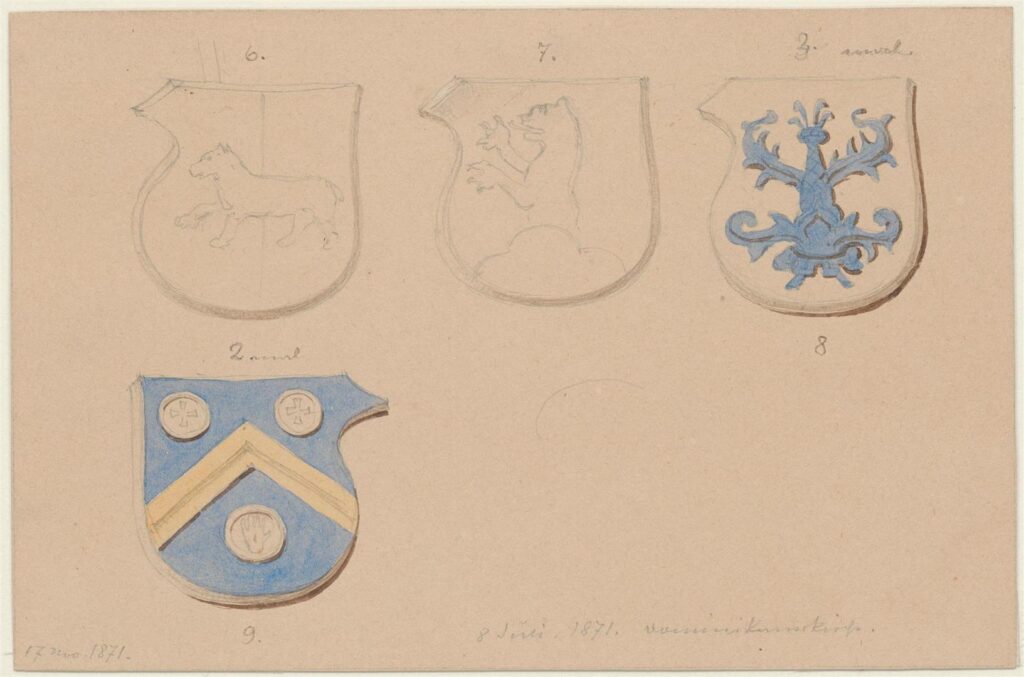

As the chest’s key had been lost over the years, Motz tasked master locksmith Laubinger to forcefully open it. This happened under the watchful eye of notary Kappes, along with two of Motz’ colleagues (Lieder and Eiszeller) acting as witnesses. The notary’s detailed records – which include both a narrative account of the forced opening and a comprehensive inventory of the contents – are preserved in the archive as H.18.02, Nr. 27, which I provide a full transcription of in the Appendix.

While the documents were transferred to the archives in 1790,35 the physical objects (including iron chest, seal stamp, fencing weapons, and funds) went to the city arsenal. Driven by the hope that this inventory might hold traces of the missing armorial charter – or the swords – I closely examined the list. Among the items were:

- A brass seal stamp used to secure the guild chest (potentially belonging to the seal discussed earlier).36

- A pair of fencing swords,37 two pairs of lined leather fencing gloves, and a pair of wooden dussacks.

- “A tin box with two locks” containing the renovated 1670 armorial grant by Emperor Leopold I, complete with red velvet covers, yellow-black ribbons, and the great Imperial seal in a red-gilded capsule.

This confirmed that the 1670 charter was still present when the archive first received the Marxbrüder materials. Whether it survived the subsequent centuries – and the devastating wartime fire that claimed half of the collection – remained the next mystery to solve.

History Repeats Itself: The 1863 Reopening and Inventory

The trail led me to the Repertorium of H.18.03 (“Charters and Records of the Societies”),38 an internal index compiled on 9 June 1863. It seems that in the seventy-five years since locksmith Laubinger had forced the lock, little effort had been made to keep better track of the replacement; the chest had sat dormant in the hall of the city scales,39 its key lost once again. Consequently, archivist Georg Ludwig Kriegk and his colleague Theodor Creizenach developed the not entirely novel idea to break open the chest and inventory its contents.40

The resulting 21 pages bear witness to the collection’s turbulent history. They include annotations from 1959 identifying which of the original 55 documents were lost during World War II, as well as a third layer of notes from 1989 documenting a subsequent reordering and repackaging of the 32 survivors. The overlapping hands (partially in German Kurrent) and the shifting archival structures made for slow, meticulous work.

A Revelation in the Repertorium

On page 13, under entry Nr. 32, I stopped short. The description matched the ominous tin box containing the 1670 augmentation exactly. A later pencil annotation reemphasized: “original charter in tin box.”41 Yet, the column that should have indicated whether the document survived the wartime fire remained conspicuously blank.

I turned back to the 1989 revision summary, which explained that the holdings had been renumbered 1–32 and were now kept in two standing boxes and one specially designed lying box. In line with updated preservation standards, the tin container had been replaced by a grey archival carton – reserved for number 32. In principle, the original augmentation should therefore still have been in the depth magazine.

The Charter Resurfaces: From Obscurity into the Records

Despite the holiday lull between Christmas and New Year, I wrote at once to the wonderfully proactive Reading Room team at ISG Frankfurt. They replied just as quickly: the piece had already been set aside for me to examine in early January 2026.

And with that, my earlier research came full circle. A document long hidden was once again accessible. I hope that bringing it back into view will ease future work on the Marxbrüder – and perhaps inspire new questions.

Conclusion: Both Marxbrüder Armorial Grants Recovered

With the resurfacing of the original armorial augmentation, both Marxbrüder armorial grants – 1541 and 1670 – are now securely documented. The charter’s transcription and heraldic analysis clarify the form, meaning, and context of this augmentation, while its reconstructed archival history sheds light on the turbulent path this significant piece has taken.

Its renewed availability – and this article – will, I hope, encourage further research on the Marxbrüder and the broader martial culture of the Holy Roman Empire.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider a donation to help fund my continued research on the Marxbrüder.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to the Institut für Stadtgeschichte (ISG) Frankfurt for their exemplary support. My sincere gratitude goes to Michael Matthäus, Head of the Old Department (Alte Abteilung), as well as the entire teams of the Reading Room and the Old Department. In particular, I wish to thank Lukas Mayeres for swiftly facilitating access to the archival material and clarifying image rights, and Pia Kühltrunk for kindly coordinating next steps in digitizing this piece for public availability.

This research has also been greatly inspired by my cordial exchange with Sabine Kindel (Archival Pedgagogy) and her excellent talk on the brotherhood’s history at the ISG on 26 May 2025. Similarly, I owe a special thanks to Eric Burkart of Trier University for his patient and inspiring counsel; I am grateful that the has consistently tolerated – and even encouraged – my frequent “archival revelations,” regardless of whether they arrived as formal inquiries or in meme format.

I am also grateful to the Polytechnic Society Foundation for the District Historian (Stadtteil-Historiker) program, within which I wrote this article. In particular, I thank Oliver Ramonat and Katharina Uhsadel for their guidance and encouragement.

My appreciation extends go to Kevin Maurer and Christopher van Slambrouk, whose podcast episode on the Marxbrüder coat of arms (featured in The Fencing Grounds) sparked my initial curiosity to investigate these heraldic achievements in such depth.

Finally, I would like to thank Cathrin Rieger for her unwavering support and encouragement throughout this project.

Appendix and Transcriptions

My transcription of the Marxbrüder Armorial Augmentation (ISG FFM H.18.13. Nr. 32)

[2r]

WIR Leopold von Gottes gnaden Erwöhlter Römischer Käÿßer zu allen Zeitten Mehrer des Reichs in Germanien, zu Hungarn, Böheimb, Dal⸗matien, Croatien und Sclavonien etc. König, Ertz⸗hertzog zu Osterreich, Hertzog zu Burgund, zu Bra⸗bant, zu Steÿr, zu Karnten, zu Cräin, zu Lützenburg, zu Württemberg, Ober und Nieder Schlesien, Fürst zu Schwaben, Marggraff des heÿligen Römischen Reichs zu Burgaw, zu Mähren, Ober⸗ und Nieder Laußnitz, gefürster Graff zu Habspurg, zu Tÿrol, zu Pfirdt, zu Kÿburg und zu Görz, Landtgraff im Elsaß, Herr auf der Windischen Marck, zu Portenaw und zu Salins etc.

Bekhennen für Uns und unsere Nachkommen am heÿl. Reich öffentlich mit diesem Brieff, und thuen kund allermänniglich, daß Uns Unsere den 20. Martÿ 1670. und des Reichs liebe getreẅe N: Meistere des langen Schwerdts und der Militarischen Exercitÿ Kunst erfahrne von St: Marco und Löwenbergen in underthänigkheit zu vernehmmen gegeben, was gestalten Ihnen ein adelicher Wappenbrieff von

[2v]

weÿland Unßerem herrn Vetter und Vorfahren Kaÿ⸗ser Carl dem fünfften, glohrwürdigsten andenkhens underm dato Regenspurg den dreÿzehenden Maÿ des fünffzehenhundert ein und vierzigsten Jahrs ertheilet worden, allermasßen Uns Sie solchen in beglaubter formb und abschrifft vorbringen lasßen, und von worth zu worth geschrieben stehet und also lautet.

WIR Carolus der Fünffte von Gottes gnaden Römischer Kaÿser, zu allen Zeiten Mehrer des Reichs, König in Germanien, zu Castilien, zu Arragon, zu Legion, beeder Sicilien, zu Hierusalem, zu Hun⸗garn, zu Dalmatien, zu Croatien, Navarra, zu Gra⸗naten, zu Tolleten, zu Valentz, zu Gallicien, Majori⸗carum, Hispalis, Sardiniæ, Cordubæ, Corsicæ, Murtziæ Giennis Algarbien, Algeciræ zu Gibraltaris, und der Insulen Canariæ, auch der Insulen Indiarum und Terræ firmæ, des Meers Oceani etc. Ertzhert⸗zog zu Österreich, Hertzog zu Burgund, Lotterich, zu Braband, zu Steÿr, zu Kärndten, zu Cräin, Limpurg,

[3r]

Lützemburg, Geldern Wirtenberg, Calabrien, Athenarum Neopatriæ, Graf zu Habspurg, zu Flandern, zu Tÿ⸗rol, zu Görtz, Parsiloni, zu Arthois, zu Burgund, Pfalzgraffzu Hanigau, zu Holland, zu Seeland, zu Pfierdt, zu Lÿburg, zu Namur, zu Rosßilion, zu Ceritan und zu Zutphen, Landgraff in Elsaß, Marggraff zu Lurgaw, zu Oristein, zu Gotiani, und des heÿligen Römischen Reichs Fürst zu Schwa⸗ben, zu Catalonia, Asturia, Herr in Frieß⸗landt auf der Wendisch Marck, zu Portenaw, zu Biscaia, zu Molin, zu Salins, zu Tripoli, und zu Mecheln etc. Bekennen öffentlich mit diesem brieff und thun kundt allermännig⸗lich, daß Wir gütlich angesehen, und betrachtet, Unsere und des Reichs getreẅe N. Meister des langen Schwerdts, und der Brüderschafft Sanct: Marco, solcher Ehrbarkeit, Redtlichkeit, Mannheit, guetter Sitten, Tugendt und vernunfft, im Kempffen und Stechen, sich bey dem heÿligen Reich bißher erzeigt und bewiesen, auch vor Unserer Kaÿl: Maÿl: berühmt worden, und

[3v]

sonderlich die getreẅen willigen dienste, darzu Sie gegen dem heÿligen Reich bißher gethan, und hin⸗führo in künfftige Zeit wohl thun mögen und sollen, und haben darumb mit wohlbedachtem muth, guetem rath und rechtem wissen den Meis⸗tern des langen Schwerdts und ihren Nachkom⸗men dieses nachgeschriebene Wappen und Cleÿ⸗nod, mit nahmen einen schwartzen Schildt, unden mit dreÿen gelben bergen, mitten des Schildts ein gelber Löw mit flüegeln, oben des Kopffs ein Schein, stehend mit den hindern zweÿen füssen auf den bergen, und haltend in der linkhen Vordern hintersich aufwerts ein Schwerdt, und auff dem Schildt ein offener Helmn, auff dem Helm ein goldfarben Cron, auff der Kron ein halber Löw mit flüegeln, oben des Kopffs ein Schein, und haltend in der linkhen Vordern hinder sich auffwerths ein Schwerdt, alß dan dieses Wappen und Cleÿnod in mitte des gegenwertigen Unsers Kaÿserlichen brieffs gemahlt, und mit farben

[4r]

eigentlich ausgestrichen, von neẅem genediglich verliehen und gegeben, Ihnen das also von neẅen auß Römischer Kaÿserlicher Macht⸗Vollkom⸗menheit wissentlich in Krafft dieses brieffs, setzen und wollen, daß nun hinführo die genante Meister des Schwerdts und deren Nachkommen für und für ewiglich, dis iezt bestimbte Wap⸗pen und Cleÿnod haben und führen, der in allen und jeglichen ehrlichen und redtlichen Sachen unnd geschäfften zu schimpf und ernst, mit streitten, kempffen, stechen, fechten, Pannieren, gezehlten auffschlagen, Insiegeln, Pettschafften, Cleÿnoden, be⸗gräbnüssen, und sonsten nach Ihren nottürfften willen und wohlgefallen, auch alle und ieder ehr, würde, gnadt, freÿheiten, Urthel und recht und gerechtigkeit haben, gebrauchen und geniessen sollen und mögen, mint Ämptern und Lehen zu tragen, zu haben, Lehen gericht und Recht zu besizen, Urtheil zu schöpffen, und recht zusprechen, und darzu taüglich schicklich und guet zu sein, in allen gäistlichen

[4v]

und weldtlichen Ständen und Sachen, alß andere Unser und des Reichs Lehens und Wappens genoß Leuth, so solches alles haben, und sich des, auch ihrer Wappen uns Cleÿnod gebrauchen und geniessen von recht oder gewohnheit von Aller⸗männiglichen ungehindert.

Vnd gebithen darauff allen und ieglichen Unseren und des Reichs Churfürsten, Gäistlichen und Weltlichen, Prælaten, Graffen, Freÿherrn, Rit⸗teren, Knechten, Haubtleüth, Burgeren, Landtvögten, Vitzthumben, Vogten, Pflegern, Verwesern, Ambt⸗leüthen, Schultheissen, Burgermeistern, Richtern, Räthen, Kündiger der Wappen, Ehrholden, Presenaten, Burgeren und Gemeinen, und sonst allen anderen Unsern und des Reichs Unterthanen und Getreẅen in was würden Standts oder wesens die seindt, ernstlich und festiglich von Römischer Käÿserlicher Macht mit diesem brieff, und wollen daß Sie die genandten Meister des Schwerdts und ihre Nachkommen, für und für ewiglich an den obberürten Wappen, Cleÿnod und freÿ⸗

[5r]

heiten, damit Wir Sie begabet haben, nicht hindern, sondern Sie deren vorgeschriebener massen, und gänzlich darbeÿ bleiben lassen, verbleiben und darwieder nicht thun, noch jemand andern zu thun gestatten, in keinerleÿ weiße, alß lieb einem ieden sey Unser und des Reichs schwere ungnadt, darzu einer Pön, nemblich zehen Marck löttiges goldts zu vermeiden, die Ein ieder, so offt er freventlich darwider thäte, Uns halb in unser und des Reichs Cammer, und den andern halben theil den offtgemelten Meistern des Schwerdts und ihren Nachkommen unnachläßlich zu bezahlen verfallen sein solle, doch anderen die vielleicht den obgeschriebenen Wappen und Cleÿnoden gleichführten, ahn Ihren Wappen und Rechten unvergrifflich und unschädlich.

Mit Uhrkundt dieses Brieffs versiegelt mit Unserem Kaÿserlichen anhangenden Innsiegel. Gegeben in unser und des heÿligen Reichs Statt Regenspurg

[5v]

am dreÿzehenden tag des Monaths Maÿ, nach Christi Unsers Lieben Herrn und Seeligmachers geburt, im fünffzehenhundert ein und vierzigsten, Unsers Käÿserthumbs im Ein und zwantzigsten und Unseres Reichs im Sechs und zwantzigsten. Ad Mandatum Domini Imperatoris.

Und Unß darauff obernante N: Meistere des langen Schwerdts, und der militarischen Exercitÿ kunst erfahrne von St: Marco, und Löwenbergen, die⸗wüetiglich angerueffen und gebetten, daß wir alß ietz Regierender Römischer Käÿser, Ihnen obinserirten Brieff, gnad und freÿheiten in allen seinen inhalt mäinung und begreiffungen zu erneẅern, zu confirmiren und zu bestättigen, wie auch zu vermehren, genediglich geruheten, daß Wir angesehen solche ihre dieswürtiger zim⸗liche bitt, und insonderheit derselben ehrbahrkeit, redtlich⸗keit, mannheit, guete sitten, tugendt und vernunfft in kempfen, streitten und stechen, auch die getreẅe willige dienste so Sie bißhero gegen Uns und dem heÿligen Reich

[6r]

gethan und hinführo noch ferners zu thuen, des underthänigsten erbiethens seint, auch wohl thuen können, mögen und sollen, und darumb mit wohlbedachtem mueth, guetem rath und rechtem wissen, mehrerwehnten Vnsers in Gott ruhenden Herrn Veters Käÿser Carls deß fünfften, ihnen ertheilten Adelichen Wappenbrief, gnad und Freÿheiten, alles seines innhalts, nicht allein genediglich erneẅert, confirmiret und bestättiget, sondern solch ihr adeliches Wap⸗pen und Cleÿnod auch nachfolgender masßen vermehrt, geziert und verbessert, und ihnen und ihren Nachkommen solches hinführo eẅiglich also zu führen und zu gebrauchen, genediglich er⸗laubt und gegönnet; Alß mit nahmen ist ein quartierter Schildt, desßen hinder under, und vordere obertheil oder feldt schwartz, unden mit dreÿen gel⸗ben bergen, darin erscheinet fürwerths ein gelb oder goldtfarber fluegender Löw mit außschlagender Zungen, außgebreiteten flüegelen, doppeltem schwanz, an der stirn mit einem Creütz bezeig⸗net, bekrönet mit einem grüenen Lorber Crantz, und

[6v]

oben des Kopffs einen gülden Schein herumb, stehend mit den zweÿen hinderen füesßen auf den hindern Zweÿen bergen, und haltend in der linkhen vordern under sich eine auff dem dritten berg ruhende weiß gestraiffte marmelsteinere saüle, in der rechten vordern auffwerths mit der spitzen hinder sich zum streit ein bloser Seebel mit vergüldtem Creütz und Knopff; vor⸗der under und hindere ober veldung himmelblaw mit rubinfarben vermischt, darinnen sechs Creützweiß geschräncktte Turniers Lantzen mit ihren spitzen über sich, dreÿ derselben zur rechten, und dreÿ zur linckhen seithen, in deren mitte steckhet auffrechts an einer langen stangen ein rother zurgespitzter blueth fahn, mit einem gülden Creütz bezeichnet, alle in der mitten mit einem rothen bandt, maschenweiß, zusammen gebunden, deren enden abwerths fliegen, in der mitte des quartierten Schilds erscheinen von beeden seithen gegen einander auß einer wolkhen zweÿ roth angethane manns armben, mit weisßen überstulpen, die halten in der mite des Schilds, mit zweÿ zusammen geschlossenen händen ein bloeses

[7r]

schlachtschwerd auffwerths mit der spitzen biß ahn den

[colored armorial depiction]

offenen Adelichen Turniers helmb, mit einem rothen

[7v]

schafft, guldenen Creütz und Knopff, ahnstatt deß schildts an dem schwerd an beeden seithen mit dop⸗pelten gelben Adlers flüegelen, deren schosßen auß⸗werths, auff dem Schild ein freÿer offener adelicher Turnirshelmb zur linckhen mit roth⸗ und weisßer, rechten seithen gelb⸗ und schwarzer helmbdeckhen, und darob mit einer gelben oder goldtfarben Königlichen Cron gezieret, darauff erscheinet der unden im schild beschriebene gantz gelb oder goldtfarber flüegender Löw mit außgeschlagener Zungen, außgebräiteten flüegelen, doppeltem Schwantz, ahn der stirn mit ei⸗nem gulden Creütz bezeichnet, gekrönet mit einem grüenen Lorber krantz, und oben umb den Kopff einen gulden schein, stehend mit den hindern zweÿen füesßen auff der Cron und haltend in der linkhen vordern eine under sich auf der Cron ruhende weiß⸗gesträiffte marmelsteinere saüle, in der rechten vordern Clawen aber, auffwerths hinder sich zum streitt ein blosßes schlachtschwerd mit vergüldtem Creütz und Knopff und blueth rothem schafft; Als dan solch ver⸗merth, gezierdt und verbesßertes adeliches Wappen

[8r]

und Cleÿnod in diesem unseren, libellsweiß geschrie⸗benen, Käÿserlichen Brieff auff dem sechsten blath, ers⸗ter seithen gemahlet und mit farben äigentlicher auß⸗gestrichen ist. Thuen das von neẅem erneẅern, con⸗firmiren, verbesßern und vermehren auß Römischer Käÿserlichen macht volkommenheit, wisßentlich in Krafft dieses brieffs und mäinen, setzen und wollen, daß nun hinführo mehrerwente N: Meistere des langen Schwerdts und deren Nachkommen für und für eẅig⸗lich vorbeschriebenes confirmirt, verbesser⸗ und vermehrtes adeliches Wappen und Cleinod in allen und ieglichen ehrlichen und redlichen sachen und geschäfften zu schimpff und ernst in streitten, stürmen, kempffen, Thurnieren, gestechen, gefechten, veldzügen, Panniren, gezehlten auffschlagen, Insiegelen, pett⸗schafften, Cleÿnoden, begräbnüssen, gemälden und sonsten allen örthen nach ihren notturffetn, willen und wohlgefallen, auch alle und iede ehr, würde, und gnadt, freÿheitten, vortheil, recht und gerechtigkeit haben, gebrauchen und geniesßen sollen und mögen, mit ämbtern und Lehen zu tragen, zu haben, Lehen

[8v]

gericht und Recht zu besitzen, urtheil zu schöpffen und recht zu sprechen und darzu tauglich, schickhlich und guet zu sein, in allen gäist⸗ und weldlichen ständen und sachen, alß andere unsere und des heÿligen Reichs auch unserer Erbkönigreich, Fürstenthumb und Landen Lehens und Wap⸗pens genoß Leüthe, so solches alles haben und sich desßen, auch ihres adelichen wappen, Cleÿnoden und freÿheit⸗en gebrauchen und geniesßen, von recht oder gewonheit von allermänniglich ungehindert, doch Uns, dem Reich, und sonst männiglichen ahn seinen rechten und gerech⸗tigkeiten unvergrieffen und unschädlich.

Vnd gebiethen darauff allen und ieden Churfürsten, Fürsten, gäist⸗ und weldlichen, Prälaten, Grafen, Freÿen, Herzn, Ritteren, Knechten, Haubtleu⸗then, Vitzdomben, Vögten, Pflegeren, Verweeseren, Ambtleüthen, Schultheisßen, Burghermeisteren, Rich⸗teren, Räthen, Kündigeren der Wappen, Erholden, Persevanten, Burgeren und Geminden und sonst al⸗len anderen Unseren und des heÿl: Reichs auch unserer Erbkönigreich, Fürstenthumb und Landen Under⸗

[9r]

thanen und getreẅen waß würden, standts oder weßens sie seindt ernst⸗ und vestiglich mit dießem brieff und wollen, daß Sie vielervänte Meister des langen Schwerds und ihre Nachkommen, ahn obberührtem adelichen wap⸗pen, Cleÿnod und allen freÿheitten, damit Wir Sie be⸗gabet haben, nicht hindern, sondern Sie deren, vorge⸗schriebener masßen, ohne alle irrung, gerühiglich ge⸗niesßen und darbeÿ gentzlich bleiben lasßen, hierwider nicht thuen, noch das iemanden anders zu thuen gestatten in keine weiß noch weeg alß lieb einem Ieden seÿe Unßer und des Reichs schwere ungnad und straaff, darzu eine Pöen nemblich zwäinzig markh löttiges goldts, zu vermeiden, die ein ieder so offt er freventlich darwieder thäte Uns halb in unser und des Reichs Cammer, und den andern halben theil den offtgedachten N: Meisteren des Schwerds von St. Marco und Löwenbergen, und ihren nachkom⸗men unnachläßlich zu bezahlen verfallen sein solle. Mit uhrkhund dieß Brieffs besiegelt mit unserm Käÿ⸗serlichen anhangenden Innsiegel, der geben ist in Unser Statt Wienn den zwäinzigsten tag Monaths Martÿ nach Christi unßers Lieben Herrn unnd

[9v]

Seeligmachers gnadenreichen gebuhrt im sechzehen⸗hundert und siebenzigsten, unserer Reiche deß Römisch⸗en im zwölfften deß Hungarischen im fünffzehen und deß Böheimbischen im vierzehenden Jahren./.

Leopold [m.p.]

Vt. Le[o]pold Wilhelm Graff zu Königsegg. R[eichs]V[ize]K[anzler] [m.p.]

Ad mandatum Sac[rӕ] Cӕs[arӕ] Majestatis proprium

Sources for Vector Assets

| Asset | Author | License |

| Lion’s body | User: SajoR | CC BY-SA 2.5 |

| Lion’s head (crest) | User: SajoR | CC BY-SA 2.5 |

| Lion’s right paw | User: Milenioscuro | CC BY-SA 3.0 |

| Lion’s forked tail | User: MaxxL | CC BY-SA 3.0 DE |

| Laurel wreath | User: Sodacan | CC BY-SA 4.0 |

| Saber (field 1 & 4) | User: Madboy74 | CC0 1.0 |

| Lance (field 2 & 3) | User: Zigeuner | CC BY-SA 3.0 |

| Band (field 2 & 3) | User: Celtus | CC BY-SA 3.0 |

| Cross | Ariane Schmidt | Public domain |

| Clouds | Olga Salova | PD-RU exempt |

| Hands & cuffs | User: SajoR | CC BY-SA 2.5 |

| Sleeves | User: MostEpic | CC BY-SA 4.0 |

| Sword at center | User: Madboy74 | CC BY-SA 4.0 |

| Wings of sword | User: SajoR | CC BY-SA 2.5 |

| Helmet | User: LowlyLiaison | CC BY 4.0 |

| Mantling | User: Bastianow | CC BY-SA 3.0 |

| Crown | User: Wereszcyński | CC BY-SA 4.0 |

My transcription of the Marxbrüder Holdings’ 1788 Inventory (ISG FFM H.18.12. Nr. 27)

[3r]

Verzeichniß

desjenigen, was sich in der beÿ Herrn Motz des Raths befindlichen der Löbl. Brü⸗derschaft von St Marco und Löwenberg zugehörigen eisern Kiste, welche, da kein Schlüßel dazu vorfunden gewesen, im Baÿseÿn der Herren Lieders, Eiszeller, Motz, sämtlich des Rats dritter Banck allhier, und in meiner, des Endes unterschrie⸗benen Notarii Gegenwart, durch den Schloßermeister Laubinger, geöffnet worden, vorgefunden, als:

1) ein geschrieben Buch mit braunen ledernen Deckeln, auf der dritten Seiten zu lesen Navitatis Mariae 1491.

2) ein ditto in Schweinleder gebunden de Anno 1575.

3) ein ditto in Pergament de Anno 1609.

4) ein ditto gleichfalls in Pergament de Anno 1609.

5) Ein Rechnungsbuch über die Brüderschaft de Anno 1609.

[3v]

6) ein Register und Meisterbuch de Anno 1629.

sämtlich in 4fo.

7) ein blechern Schachtel mit zweÿ anhangen⸗den Schlößern, in welcher enthalten, der Brüderschaft von St Marco und Löwen⸗berg von weÿland sH Römisch Kaiser⸗lichen Majestät Leopoldo im Jahr 1670. renovirte Wappenbrief auß Pergamt mit rothen sammeten Deckeln und gelb und schwar⸗zen Banden, oben, unten und vorne gebund⸗den, woran an einer goldnen Litzen eine roth verguldete Kapsul, in welcher das groß Kaÿserliche Siegel in roth Wachs gedrückt, hänget.

8) ein Geldstock von Eisenblech mit einem Schloß, in welchem sich befindet:

{curly brackets a)–c): “das Geld ist bei L. Zeughaus[?]-Amt abgegeben worden.”}

a) das Ladensiegel in Meßing gestochen.

b) 13 fl. 50 xr. in einem inwendig beschrie⸗benen Papier eingewickelt, bestehend: in dreÿ Ducaten und alten Münzen.

c) 14 fl. in einer Duᵒtten ebenfalls in alter Münze.

[4r]

9) Verschiedene alte theils auf Pergament theils auf Papier gedruckte Artickeln.

10) Ein länglich hölzernes Futteral, darin⸗nen die Privilegia confirmatoria der Löbl. Brüderschaft von weÿl. Ihro Römisch-Kayserl. Majestät Friedrich an bis auf Leopoldum, zweÿmal, zusammen gebunden, woran ein Capsul mit der Stadt Frankfurt Insiegel hän⸗get, sich befinden.

11) verschiedene Meister Briefe.

12) verschiedene auf Pergament geschrie⸗bene Privilegien.

13) verschiedene Avis Briefe, so die Bruderschaft sich einander zuge⸗schrieben.

Auser obig. specificirten und in der Kisten befindlichen Stücken, gehörn noch dazu und sind noch vorrätig:

[4v]

{curly bracket 14)–16): “sind auf Lobl. Kriegs⸗Zeug Amt gekommen.”}

14) Ein paar Fecht Schwerder.

15) zweÿ paar lederne gefütterte Fecht⸗handschu in einem Sack.

16) ein paar hölzerne Triseeken.

Daß obige Stücke von mir Endes unter⸗schriebenen richtig aufgezeichnet und nach⸗gesehen worden; ein solches attestire hiermit pflichtmäsig.

geschehen Franckfurt am Maÿn den 10. January 1788.

Johann Friedrich Kappes,

Kaiserlich geschworner und dahier immatriculirter Notarius.

- For example, when I informed Eric Burkart of Trier University about the find, he remarked that he had already come across the piece – which, in hindsight, should not have surprised me – though without the opportunity to study it further yet. ↩︎

- My main takeaway is that the most effective way to discover whether an archival source might exist somewhere is simply to ask. Not all holdings are fully catalogued, and every archivist I had the pleasure of working with (including in Frankfurt) was unfailingly kind, knowledgeable, and extraordinarily helpful. ↩︎

- I am indebted to the exemplary support of ISG Frankfurt, in particular the Old Department – especially Pia Kühltrunk for taking the time to discuss the matter in depth, and the head of the department, Michael Matthäus. It may still take a couple of weeks until the reproduction is freely available. ↩︎

- The trail was longer than anticipated. For the detective story of how this charter remained hidden in plain sight, see the “Archival Journey” section toward the end of this article. ↩︎

- I am grateful to the Reading Room team – Georgina Lienhard, Lukas Mayeres, and Kevin Stumpf – for promptly retrieving this and other items from the depth magazine, providing swift access to the material, and patiently answering a series of very specific questions. ↩︎

- “Leopold, by the grace of God elected Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor Augustus, King of Germany, Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, / Slavonia etc. Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, and Württemberg, etc., Count of Tyrol, etc.” ↩︎

- “We, Leopold, by the grace of God elected […]” ↩︎

- AT-OEsTA/HHStA RHR Grat Feud Conf. priv. dt. Exp. 48-3-1, p. 225 ff. After I commissioned digitization of this item in October 2025 and requested full digitization in November 2025, the House, Court and State Archive made the entire convolute accessible, including the Federfechter material under 48-4-1. This constitutes a significant resource for future research on the two fencing societies. The Marxbrüder convolute (436 pages, 1558–1675) remains the most substantial collection outside the Frankfurt holdings and is essential for contextualizing the Imperial privileges. It also includes an ornate and remarkably well-preserved 1580 transumpt of Charles V’s 1541 armorial grant. ↩︎

- The charter I had found in Basel (PA 111 1) appears to be an original, though the missing seals and signature leave some uncertainty. ↩︎

- H.18.03 Nr. 32., fol. 9v. ↩︎

- H.18.03 Nr. 32., fol. 5v. ↩︎

- H.18.03 Nr. 32., fol. 5v. ↩︎

- H.18.03 Nr. 32., fol. 6r. In the Holy Roman Empire, these three words were the “magic formula” for an armorial augmentation (“Wappenbesserung”). ↩︎

- AT-OEsTA/HHStA RHR Grat Feud Conf. priv. dt. Exp. 48-3-1, p. 227 ff. (fol. 2r ff. of the concept). See my second article for an in-depth discussion. ↩︎

- Literally: “hind lower and fore upper part or field.” ↩︎

- Literally: “yellow or golden” ↩︎

- Literally: “fore lower and hind upper quarter.” ↩︎

- Original: “himmelblaw mit rubinfarben vermischt.” I have not yet encountered this unusual paraphrase for “blue” (Azure). ↩︎

- Original: “lange Stange” Although the blazon repeatedly mentions this polearm rather than a lance for the center, it appears indistinguishable from the other lances in the colored depiction, the later monochrome copy, and the concept. I therefore conclude that a “lange Stange” with a pennon is simply a banner lance and not depicted differently from the surrounding jousting lances. ↩︎

- Heraldic directions follow the perspective of the shield-bearer, so left and right appear reversed to the viewer. ↩︎

- Original: “Schlachtschwert” ↩︎

- See my analysis of the Viennese concept RHR Grat Feud Conf. priv. dt. Exp. 48-3-1 (p. 227 or fol. 2v ff. for the blazon, and p. 241 or fol. 5r for the armorial illumination). ↩︎

- Probably Vice Chancellor Königsegg, who is also the second signatory. ↩︎

- I developed this idea when visiting the excellent special exhibition on printer signs at Gutenberg Museum Mainz. It remains on view until 22 February 2026, and I warmly recommend a visit. ↩︎

- H.18.03 Nr. 32, fol. 6r. ↩︎

- In Antiquity, the Strait of Gibraltar was identified with the Pillars of Hercules, marking the finnis terrae or boundary of the known world. ↩︎

- Adapted from Ruscelli (1584): “Le Imprese Illustri del Leronimo Ruscelli”, p. 103, “Carlo Quinto Imperatore.” ↩︎

- A team around Jens P. Kleinau had done this, including Dorothee Klein, Daniel Burger and others. Wener Ueberschär was among the initiators. If I find the time, I may supplement this with a similar inventory of ISG FFM H.18.03, the second Marxbrüder archival collection. ↩︎

- Hils, Hans-Peter (1985): “Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes,” p. 175. ↩︎

- In retrospect, this made perfect sense: the charters had been separated from the other privileges and stored elsewhere, effectively invisible to anyone relying on the usual references. ↩︎

- For protocols on those assets (mostly dating from the 16th century), see the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations in the Medel Fechtbuch (Cod.I.6.2º.5). ↩︎

- H.18.02, Nr. 25. ↩︎

- H.18.02, Nr. 13, fol. 33r. ↩︎

- ISG Frankfurt contains more sources on him, e.g., his election as sworn guild master of the baker’s trade (H.02.14, 1785-IV). ↩︎

- cf. H.18.03 “Bestandsgeschichte”. ↩︎

- Alternatively, it could be the second seal appearing on several letters in the Marxbrüder holdings (e.g., H.18.03. Nr. 7), which shows their 1541 arms – or an entirely different, yet unknown one. ↩︎

- What is referred to by the HEMAism “Feder(schwert)” today. The period-accurate term is indeed Fechtschwert. ↩︎

- The taxonomy of the ISG FFM lists the two Marxbrüder archival collections under “Fencing Societies of the Marxbrüder and Federfechter,” although almost all documents pertain to the Frankfurt-based Marxbrüder. ↩︎

- cf.“Bestandsgeschichte“ of H.18.02. ↩︎

- ISG FFM Repertorium 168, p. 1. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 13. ↩︎