This article is also available in German.

Marxbrüder in Frankfurt: Sites of Memory 🗺️ Part I

The Brotherhood of Our Dear Lady, the Pure Virgin Mary, and the Holy and Mighty Prince of Heaven, Saint Mark – as it is called with a certain verbosity in the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations – was affiliated with the town’s Dominican Monastery at least from the middle of the 15th century to about 1525.1

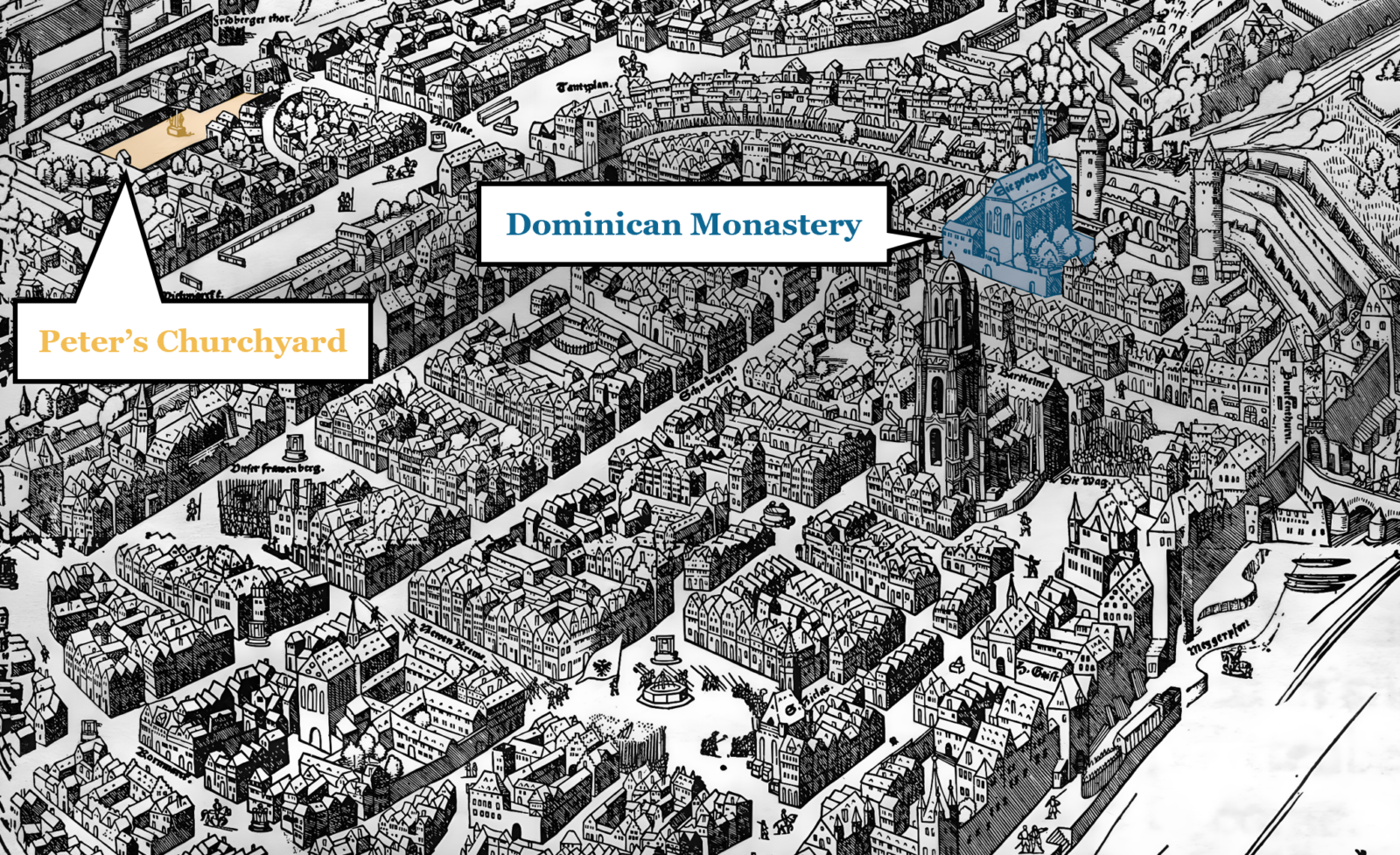

We’ll explore this affiliation in the first half of this article. In the second part, we’ll move to Peter’s Churchyard to the north-west of this monastery. It is this place that gave rise to events which would not only end this affiliation, but also leave a lasting imprint on Frankfurt’s municipal history.

Below, you see a map of the old town of Frankfurt as it would have looked back then, marked with these two locations.

Frankfurt on the Verge of Modernity

From the late Middle Ages to early modern times, Frankfurt was home to around 10,000 inhabitants,2 making it a medium-sized German city. However, its significance dwarfed its size by far: It served as the electoral city for Holy Roman Emperors and the established coronation site from the mid-1500s onward.

Located at the heart of German-speaking lands, Frankfurt also was a central trade hub with the Low Countries, France, and Italy. This reflected in the biannual trade fairs, one around Easter and another in September, attracting vast streams of merchants and craftsmen from nigh and far. These fairs were massive public events that could double the city population3 for the three weeks they lasted. In that time, people made deals, attended church service, ate, drank, celebrated – and fenced. It is during those fairs that the Marxbrüder – a decentralized fencing guild of craftsmen – met.

Guild Origins in the Dominican Monastery

The earliest known organizational form of the Marxbrüder was a religious confraternity, affiliated with the Dominican monastery in Frankfurt. The Frankfurt Fencing Regulations in manuscript Cod.I.6.2º.5 – better known by the more easily spoken name “Hans Medel Fechtbuch”4 – provide a detailed account what this affiliation looked like. They also contain rules for becoming a master of the sword, electing a captain, and the involved fees and penalties in case of transgression.5

Confraternity Structure and Religious Services

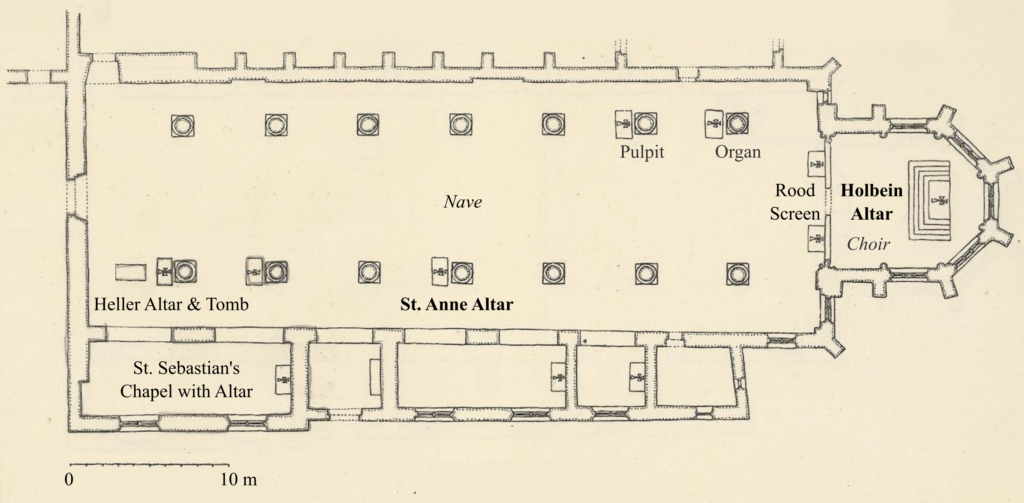

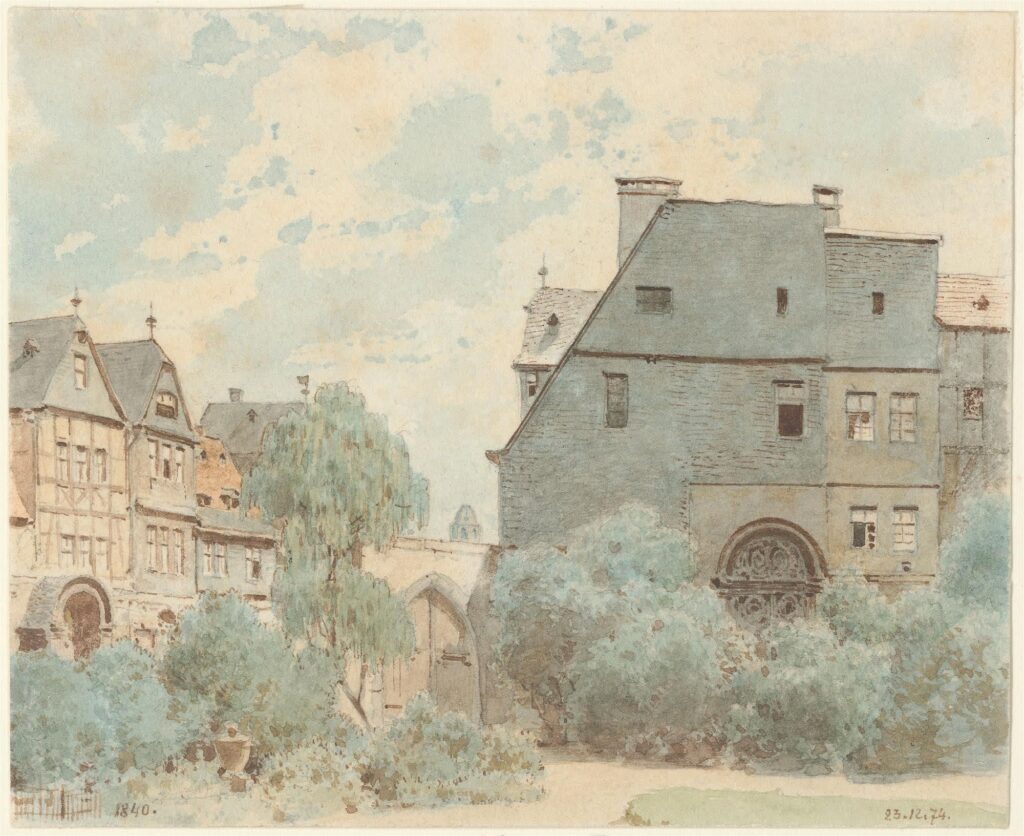

This monastery was an old and eminent institution to the north-east of the town center, divided by the old fortifications from the Jewish quarter.6 In exchange for payment to the Dominican order, the brotherhood was entitled to “magnificent and splendid” chanted Masses in honor of their patron Saints Mary and Mark. These took place in the choir of the Dominican church – which was dedicated to the virgin Mary7 – on and around her Nativity in the first half of September. This also was precisely the time of the main meeting of the brothers at the trade fair.8 Apart from spoken masses each quarter and at All Souls’ Day, a requiem Mass in honor of the deceased brothers took place the day after Nativity. The monastery also housed a grave of the brotherhood (either in the church or the cloister)9 which the sacristan maintained and adorned with candles.

This establishes that the fates of the Marxbrüder and the Frankfurt Dominican monastery were interwoven. Confraternities such as this one were quite common among craft guilds or other civilian organizations: The monastery could generate steady revenue for operations and investments, such as new buildings or the acquisition of books and art.

On the other hand, the civilians could consolidate their finances to cover honorable funerals, prayers for the deceased, and regular masses – for salvation and public reputation. Beyond these spiritual services, confraternities also helped insure health or legal costs of their members. To set things in relation, let’s have a closer look at the cost for these religious services: the two festive masses around St. Mary’s Nativity cost 8 Shillings – paid by the brotherhood’s captain to the Dominicans – and the more modest six spoken masses cost half of that.10 Therefore, a sung mass would have cost a craftsman several days to weeks of wage.11 These expenses illustrate the collective burden that confraternities shouldered to make such services accessible to ordinary craftsmen. In contrast to this, the more affluent Frankfurt patrician families such as the Hellers and Holzhausens could pay for these benefits on their own – and did so ostentatiously.

New Archival Traces – Why the Guild is Older Than Assumed

Thanks to the restless work of the Dominican Jacquin around three centuries later, we find backtraces to the Marxbrüder in the monastery’s records. The preacherman who “wrote much […] and was never idle”12 had catalogued the monastery’s entire, formidable library,13 and wrote a chronicle on the order’s history in Frankfurt. Within this Succinctum Chronicon Praedicatorum, there is a copy of a Liber Animarum with a list of civilian confraternities and donors of the monastery.14 Among these also appear the fencers.

I had the chance to examine this original source at the Institut für Stadtgeschichte (ISG) Frankfurt myself and can confirm earlier findings: St. Mark’s brotherhood appears at the end of a 1458 enumeration of donating confraternities to be commemorated during the Dominican’s prayers of intercession.15 Apart from a laconic “[commemorate] the fencing masters, who are in St. Mark’s Brotherhood”,16 an entry dated to 1476 also confirms the cadence of masses provided in the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations, notes fluctuations in the guild’s financial contributions, and that – for economic reasons – masses could be transferred from the choir to the nave, or that chanted masses could be toned down to spoken form.

The text also refers to old agreements predating the reform of the Dominican convent in 1474, reinforcing that the brotherhood is older than the oft-cited first certain attestation in that same year,17 and perhaps even older than the earlier mention of 1458. More material could be found in this source, which I so far could only study in samples – the “succinct” chronicle spans five massive codices, each densely written in ecclesiastical Latin with the occasional German fragment.

👉 If someone wanted to continue this endeavor, I would recommend focusing on the first book (ISG H.13.14, Nr. 16), and looking out for the key words “schirmmeister” (“fencing masters”) or “dimicatores” (“fighters”), which is how the guild is referred to in the source text.

With Sword and Pretzel: Peter Weißkirch – Guild Captain and Baker

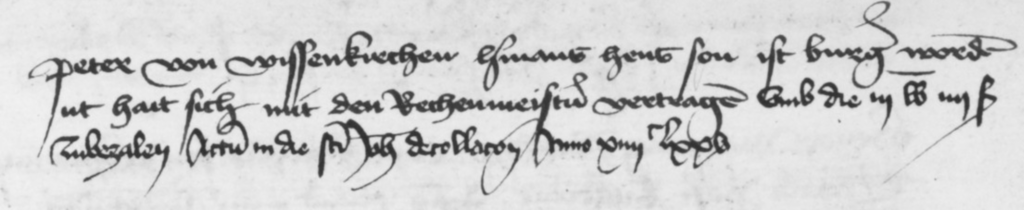

It was around this time that the commoner Peter from Weißenkirchen makes his first appearance in Frankfurt’s records: A fencer and baker, he borrowed the funds necessary to become a naturalized citizen of Frankfurt from his guild masters – thus leaving behind his humble beginnings in 1475. This step laid the foundation for his rise as captain of the Marxbrüder and a respected military leader.

In 1487, the Marxbrüder received their first imperial privilege from Frederick III.20 The following year, Peter Weißkirch commanded Frankfurt soldiers under the same Emperor to rescue his son Maximilian from Flemish rebels in Bruges.21 Weißkirch’s coat of arms – upward-crossed swords beneath a pretzel and flanked by stars – appears on his military letters of employment,22 symbolizing his dual life as a master baker and sword master, bound to defend his city and Emperor.

Weißkirch appears as one of the signatories of the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations in 1491, and even became captain of the Marxbrüder from 1494 to 1496.23 Although the guild convened in the Imperial city, its decentralized nature made local captains the exception, rather than the rule. In the closing year of the century, the captain again took the field during the Swabian War against the Swiss Confederacy.24

From commoner to citizen – navigating multifaceted roles as a baker, fencer, and captain – Weißkirch’s trajectory illustrates how Frankfurt’s guilds provided crucial pathways for advancement to ambitious newcomers.

The Marxbrüder Amid Patronage and Power

While Weißkirch exemplifies the opportunities afforded by Frankfurt’s guilds like the Marxbrüder, these organizations operated within a broader urban and religious landscape. The Dominicans, whose monastery was home to the fencers’ confraternity, turned these affiliations into lasting economic and cultural influence.

Beyond common taxes and rents, the patronage of confraternities and patricians secured steady revenues for the order. As a result, the monastery accumulated great wealth: In the late 15th century, the church’s choir – where the brotherhood celebrated its masses – was rebuilt in late Gothic style, including delicate tracery windows and elaborate net vaulting.25 Throughout the church, the rib vaults were painted in vivid colours, carried by golden column capitals on the wall.26 By the early 16th century, the monastic library was the biggest in town,27 and the church decorated with splendid works by renowned artists.

The high altar dedicated to Mary was enriched with paintings from Hans Holbein the Elder’s workshop, transforming it into a magnificent winged piece. More modestly, an altar dedicated to St. Anne – which may have been financed from pooled contributions by the confraternities, including the Marxbrüder – entered the nave.28

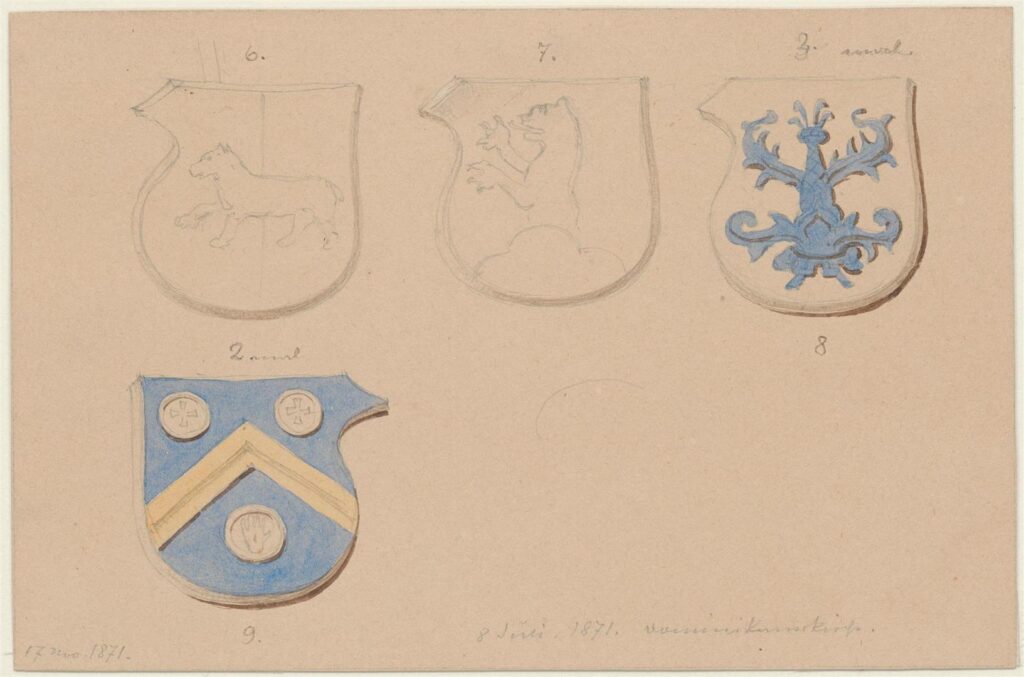

Their contributions, though less ostentatious than patrician donations, may nonetheless have left heraldic traces in the church. The coats of arms of the order’s patrons were placed as keystones at the intersections of the rib-vaulted ceiling. While I could not find arms unambiguously referencing the Brotherhood of St. Mark, one example shows notable structural parallels. Although the sketch is highly schematic – explaining the lack of tincture, and perhaps also the absence of other attributes such as mane, wings, and sword – the underlying composition is still legible. It aligns with the St. Mark lion as Marxbruder and master builder Hans Keesebrod displayed it in his personal coat of arms: A half lion upon a trimount.29

The Holbein Altar functioned not only as an outstanding work of art, but also as a vehicle of propaganda. On the outer panels, the Dominican Reginald of Orléans receives his habit directly from the Virgin Mary, a striking image reinforcing the order’s claim for spiritual authority.30 Meanwhile, the inner panels of Christ’s Passion cast the Jewish community as principal aggressors, implicitly targeting the residents of the adjacent ghetto and expressing anti-Judaic sentiment31 that was wide-spread among the Dominicans and the wider population.

In 1506, the church received its most well-known artistic treasure: a winged altarpiece from the workshops of none other than Albrecht Dürer – who even appears on the central panel – and Matthias Grünewald.32 The patrician Jakob Heller donated this piece, hence known as Heller Altar, commissioning portraits of himself and his wife in prayer at its base, flanked by their families’ coats of arms. They were later buried in the prominent position besides this altar.

I emphasize this décor not only to reconstruct how the brotherhood’s focal venue appeared, but also because it foreshadows the developments that soon severed its monastic ties – developments in which the Marxbrüder played an active role.

This patronage and art expose structural tensions in early modern Frankfurt: Patricians and wealthy clerics, including the Dominicans, concentrated immense economic and political capital. For common craftsmen (let alone lower strata of society), opportunities to be heard or to advance were small. That monasteries were largely exempt from taxation did not sit well with the narrow base of taxable citizens, among them both modest craftsmen and wealthier guild masters.

Two thirds of Frankfurt’s city council, its highest governing body, were controlled by the patrician elite, including families such as the Hellers.33 The few remaining seats went to guild artisans, themselves only a fraction of the city’s craftsmen, since just a handful of possessions were deemed eligible for council.34 This backdrop of inequality – combined with the spread of reformist beliefs – created tensions soon to erupt into open conflict between the craft guilds, the clerical establishment, and the council.

Intermezzo Digressivo: Hans Talhoffer – Another Early Marxbruder?

Before turning to the ensuing developments, it is worth pausing for a digression35 on Hans Talhoffer. For readers unfamiliar with him, Talhoffer was a prominent fencing master of the 15th century, whose illustrated fight books remain key sources on martial culture. Through shared symbolism, his persona and a newly discovered early Marxbrüder seal illuminate the guild’s formative identity. Readers eager to continue with the main arc or less interested in Talhoffer and Marxbrüder iconography may skip directly to the next section.

We have seen that the Marxbrüder were affiliated with the Dominicans already in the 1450s, and maybe even before. The surviving Frankfurt Fencing Regulations, however, contain a documentary gap before 1491, because the extant text is only a later copy of a more complete original destroyed in a fire during World War II.36 That said, we can still glimpse these lost early records through a 1877 article by Karl Wassmansdorff.37 He notes that Hans Talhoffer owed the brotherhood money for holding Fechtschulen in 1482, which suggests he was a guild member. I note this here because the question of whether Talhoffer was “possibly” or “probably” a Marxbruder prompted debate after my first article; this evidence points to the latter.

Furthermore, there are iconographic traces: Talhoffer’s coat of arms and chain show a lion of St. Mark. Earlier research by Eric Burkart (2014) and Paul Becker (2017) has already pointed to a Marxbrüder connection.38 Yet, the degree of similarity between Talhoffer’s emblem and a newly found Marxbrüder seal resembling it invites closer examination.

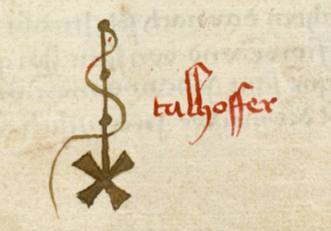

To begin with the established: The black shield shows a golden crown enclosing two downward-crossed swords. Above it rests a civilian frogmouth helmet with black-golden mantling – a common motif, though notably aligned with Marxbrüder colors.

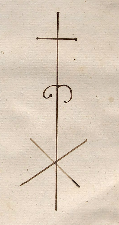

The crest features Talhoffer’s house mark, resembling a whip upon a St. Andrew’s Cross. I note that this design closely parallels the Marxbrüder house mark, which shares the same cross base and vertical, though the horizontal elements diverge in detail.

Most notably, the shield is flanked by two creatures of the Tetramorph: To the left appears an Eagle of St. John, which earlier work connected to Talhoffer’s first name,39 and which holds his personal motto: “bedenck dich Recht” (“take due thought”).

To the right, we see a Lion of St. Mark in a rather peculiar pose: Haloed and winged, it seems to stand on all fours, yet not quite grounded: its right forepaw is bent backward, grasping a longsword near the tip. The blade and pommel rise diagonally to the right, like an oversized quill with awkward balance. This posture echoes the iconography of the Lamb of God, often depicted bearing a cross or banner in similar fashion. To my knowledge, this unusual rendering of St. Mark’s lion is unique to Talhoffer – and the Marxbrüder guild.40

The remaining Marxbrüder holdings in Frankfurt contain an old seal of the brotherhood, seemingly dating back to the 15th century.41 Upon closer inspection, I noted the link to Talhoffer42 and took several pictures allowing to obtain a textured 3D model via photogrammetry – as shown here.

My 3D scan of a Marxbrüder seal (ISG FFM 18.03, Nr. 7), preceding their 1541 armorial grant and possibly from the late 15th century.43 Navigate with touch or mouse.

The seal is rendered in red wax within a wooden casing of about 5 cm diameter. An encircling inscription in Gothic minuscule reads: “unser broderschaft sant mar” (“our brotherhood saint mark”). At its center, the seal depicts the St. Mark lion in the same pose as on Talhoffer’s coat of arms and chain – on all fours, wings spread, right forepaw bent, grasping a diagonally upward longsword close to the tip.

Together with the fact that Talhoffer appeared as a debtor in the Marxbrüder records,44 this iconographic overlap is too precise to dismiss. His likely membership shows that the Marxbrüder attracted (and produced) public figures – a continuity that set the stage for their later political dealings we will turn to now.

Years of Mystery: What Happened Between 1524 and 1530?

Curiously, the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations, which otherwise record all Marxbrüder captains and masters from 1490 to 1566 in orderly succession, contain a conspicuous gap: after the election of captain Heinrich Persickh of Heidelberg in 1524,45 no further entry appears until the election of the Frankfurt burgher Laux Braun in 1530. What happened during those years to disrupt the brotherhood’s operations so profoundly?

Peter’s Churchyard and the 1525 Revolution

When Adam drew and when Eve span, where was then the nobleman?46

It was April 17 – Easter Monday – of the year 1525: The spring fair had just ended, and most of the visiting craftsmen and merchants had already left Frankfurt to rejoin their families during the feast.

The Easter Monday Riot

For the burghers of Frankfurt, however, events took a different turn:47 On Peter’s Churchyard, a cemetery toward the northern city walls, an enraged crowd had gathered. Among them likely stood Laux Braun, a young fencer and furrier.48 Their demands were sweeping: fundamental economic and religious reforms, including greater representation in the council, and the adoption of reformatory positions.

The riot did not erupt out of nowhere. In its lead-up, burghers and the clerical establishment had clashed repeatedly and with increasing intensity:50

- Spring Fair 1522: Reformist Hartmann Ibach delivered a fervent sermon in St. Catherine’s church, condemning the veneration of saints – especially of Mary, patron of the Marxbrüder – and portraying confraternities as mere clerical crutches. He urged that the wealth flowing to monasteries should be redirected to the poorest instead, which was met with “murmurs of approval.” When the council bowed to pressure from the Archbishop of Mainz and expelled Ibach, popular discontent was inflamed.51

- All Soul’s Day 1524: A circle of “Evangelical Brethren,” consisting mostly of craftsmen around theologist Gerhard Westerburg makes the first public appearance by openly challenging the Dominican lector on the doctrine of the purgatory – signaling the spread of reformist voices among citizens.

- November 1524: Another reformist preacher, Dietrich Sartorius, was exiled by decree of the Archbishop of Mainz with the backing of Emperor Charles V – later patron of the Marxbrüder’s coat of arms – intensifying reform-minded burghers’ sense of persecution.

- March 1525: The unrest boiled over into violence: the Catholic priest of the Imperial cathedral was evicted by a furious mob, a stark sign that the confrontation had moved beyond words.

But this Easter Monday of 1525 would mark the preliminary highpoint of these escalations: On Peter’s yard, the rioters took up arms and set out to storm the Dominican monastery, still the wealthiest in town. Anticipating such an assault, the friars had hidden their treasures and books.52 Instead, the crowd ransacked the ample stores of food and wine,53 while the craft guilds dispatched civil militia to seize control of city gates,54 towers, and the bridge to Sachsenhausen.

On April 19, two days after Easter Monday, violence spread further: A mob tried to ransack the Jewish quarter – an assault barely repelled by the gate guards.55 Much like the Dominican art that framed the Jewish community as responsible for Christ’s suffering, anti-Judaic beliefs were widespread in society. Conspiracy theories and propaganda reinforced the false notion that the small ghetto housed profiteers of the dire economic conditions. That same day, Our Lady’s Monastery and several cathedral prelates’ houses were looted.56

With public order collapsing, the council sought to channel the unrest into negotiation. It persuaded the rioters to formalize their demands and elect a representative body – the “61er,” dominated by guild craftsmen. Among them was again Laux Braun,57 the fencing furrier.

Laux Braun – Marxbruder and Radical Revolutionist

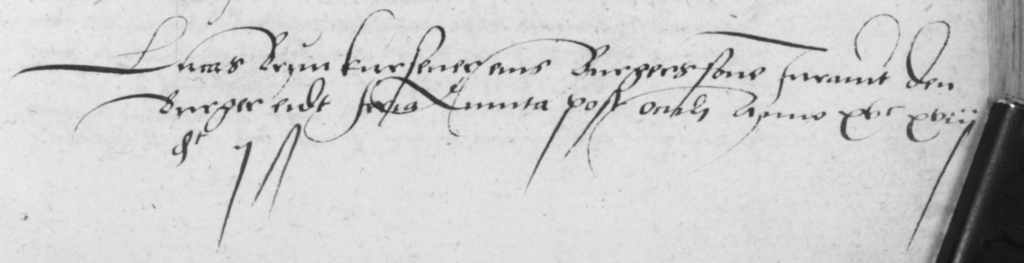

Lucas Braun, more commonly referred to by his nickname “Laux,” was a young burgher of privileged background. Born into citizenship, he became part of the furrier guild – guild artisans of high status in Frankfurt. As they were among the few crafts with a permanent seat in the council,58 the furriers had relatively high political sway. Yet, it still paled in comparison to the about 30 seats held by the patrician elite.59

Besides his profession, Braun also was a Marxbruder: He makes repeated appearances as a master and captain in the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations during the aftermath of the guild uprising.61 Although the records pause during the rebellion, we can deduce that he most probably already had been a member in those years: Only masters of the sword were eligible for captaincy, and becoming a master took years – with several preceding ranks.62

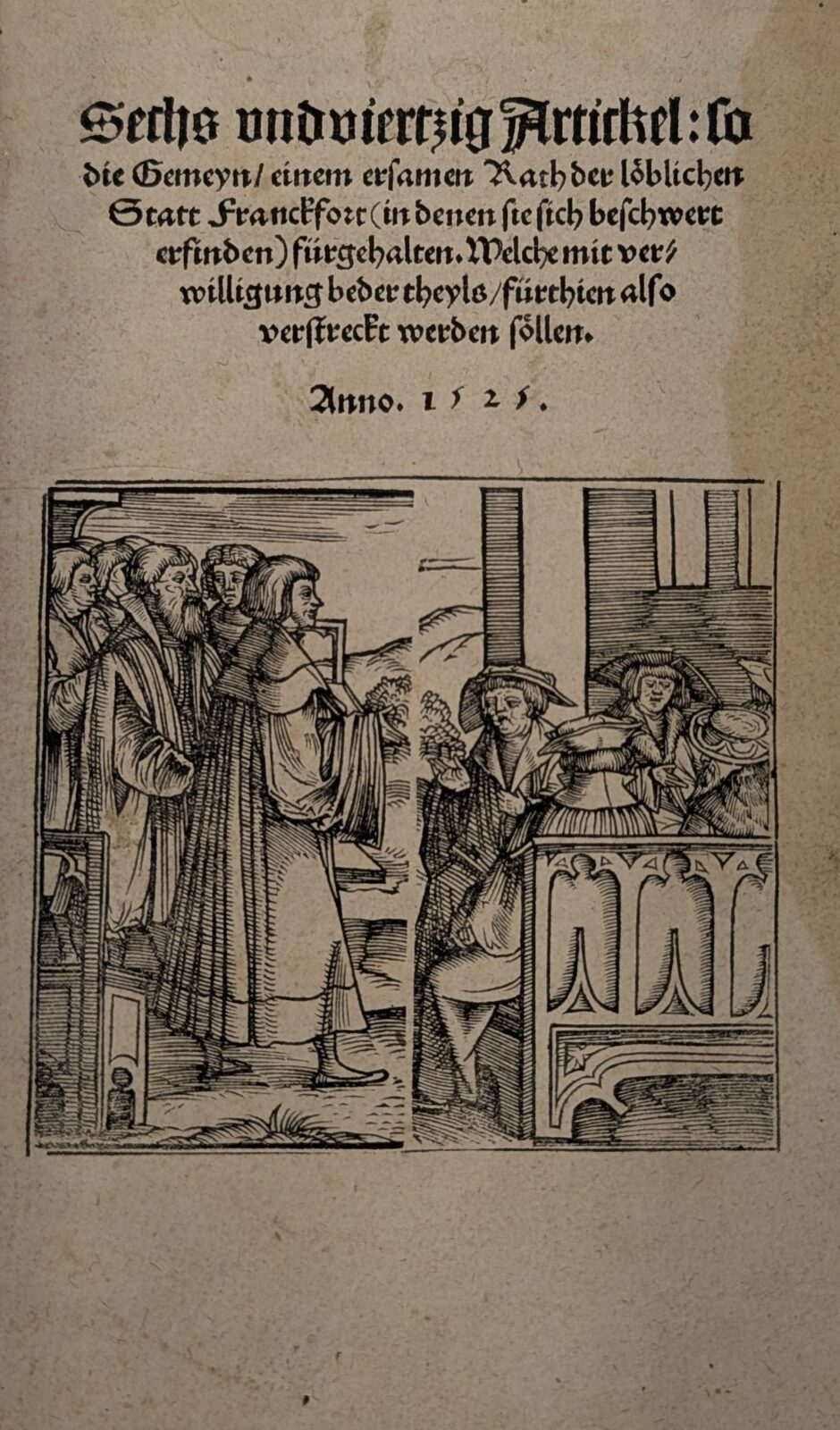

In the lead-up to the uprising, Braun aligned with the Evangelical Brethren around Westerburg and the inner circle of the revolutionaries. As a member of the elected representatives of the Frankfurt revolt – the 61er – he helped pass forty-six articles of demands to the council. Shaped by Westerburg’s reformist influence,63 the pamphlet took “Twelve Articles” spread earlier by Swabian rebels as a blueprint and eclectically expanded them. Among its additions were civic and religious reforms such as abolishing clerical tax privileges, subjecting clergy to secular courts, and the dissolution of monasteries.

In harness, armed with handguns, pikes and halberds, the revolutionists marched repeatedly through the old town, ultimately forcing the council to accept these articles on the Saturday after Easter, the 22nd of April.64 Publicly proclaiming these articles in full, and promising to fulfil them, the council requested the protesters to renew their civilian oath – public order seemed restored, at least for the moment.

Yet the concessions did not reach far enough for many: Out of the 61 representatives, ten “of the most radical of the radicals” emerged on the 25th of April. Once again, Marxbruder and furrier Laux Braun was part of those, along with the shoemaker Hans von Siegen and the tailor Niclas Wild, known as “the Warrior.” Acting as a vice squad, they raided clerics’ homes and forced them to dismiss their concubines. Driven by a fundamentalist zeal for stricter religious morality, they also threatened divorced couples with exile unless they resumed their marriages. Day after day, the radicals added new demands or sharpened existing ones among the forty-six articles.

Frankfurt at the Heart of Revolution

It would be misleading to view this revolution as a straightforward protest against “the” church or “the” council, or as a simple clash of underdogs against elites. In reality, the uprising belonged to the wider “German Peasants’ War” – which as this story shows, was neither confined to peasants nor truly a single war.65 Instead, it was a revolutionary movement that swept across southern and central German-speaking lands, the largest European upheaval before the French Revolution, leaving hundreds of thousands dead. Many of its participants – including figures like Laux Braun in Frankfurt – were in fact relatively privileged. Their demands were manifold and overlapping, combining political, economic, and religious motives. At the epicentre of this turmoil, Frankfurt emerged as one of the most important urban hubs of rebellion.66

By early May, rumors spread that the White Company – a peasant rebel force nearly equal in size to Frankfurt’s population – was planning to march on the city to pillage the Teutonic Order’s House and massacre the Jewish community.67 While parts of citizenry were willing to side with the rebels, the council strongly cautioned the guilds of grave consequences: Beyond the threat of bloodshed, the city would incur the wrath of the Imperial princes – and the Emperor himself. The punishment would likely be nothing short of losing the privileges as an Imperial city (including the annual trade fairs), and thereby suffering economic decay. Although the rebel force was crushed by imperial troops before reaching the city, the specter of its approach proved decisive in rallying Frankfurt’s guilds back to allegiance.

Settling Dust: End and Aftermath of the Uprising

While the council’s careful maneuvering gradually pacified the unrest, Laux Braun together with Niclas Wild and Hans von Siegen continued to stir up resistance. On 15 May, they gathered armed supporters at von Siegen’s house and nearly clashed with the council’s leaders and militia.68 Apparently, the confrontation was defused through the diplomatic skill of a councilman.

Yet, this resurgence was short-lived. By the end of the May, the council had ultimately reasserted its authority: it dissolved the revolutionary representative bodies – the 61er and the radical Ten – expelled the spiritual leader Westerburg from the city, and revoked the 46 reform articles.69

Nonetheless, the movement’s impact endured in two respects: A newly introduced public alms fund channeled former monastic assets (e.g., obtained from confraternities) toward the poor, and continues to operate until today. Meanwhile, the introduction of two reformed priests – Johannes Bernhard and Dionysius Melander70 – marked the transition of Frankfurt toward Protestantism.

The revolutionary leaders, including Laux Braun, remained unpunished71 – too strong was their backing in the populace. In the aftermath of the revolution, Braun became Marxbrüder captain in 1530 and held the office for three consecutive terms,72 an exceptional run that reflected his standing. During his captaincy, the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations were updated twice, and he oversaw the inventory of the confraternity’s properties at the Dominican monastery.73 The belongings – including ornate liturgical vestments, probably chalices, and perhaps figures of St. Mark – were withdrawn from the monastery in 1534, and either split among the brothers74 or transferred to the alms fund .75

This marked the end of the Marxbrüder’s confraternity with the Dominican order and coincided with a broader waning of civic donations to monasteries. Guild records from the years after the revolution also do no longer mention the Virgin Mary, suggesting that her name vanished from the brotherhood76 once their services at the Dominican monastery ceased. In 1536, Laux’ successor Blasius Velten noted that he received the guild chest with not a single coin remaining and just “a few swords.”77 Whether the money had been dispersed among brothers, absorbed into the alms fund, or lost by other means remains an unresolved mystery.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider a donation to help fund my continued research on the Marxbrüder.

Appendix

My partial translation of Cod. I.6.2° 5, fol. 7r f.

The text is written in cursive, using an early modern Franconian or Bavarian dialect, with headlines in Textura script.78 I began with the transcription by Oliver Dupuis,79 but soon turned to the facsimile of the original preserved at Augsburg University Library.80

“Firstly, we mandate as is ancient custom:81 that henceforth on all Fridays of the Ember fasts82 and on All Souls’ Day, a conventual brother appointed by the Prior shall celebrate a vigil Mass83 in the choir of the Dominican monastery84in Frankfurt. Likewise, on the day after the Nativity of Mary, a requiem Mass85 shall be read for the souls of our deceased brothers and of all the faithful.

For this, the acting captain of the brotherhood shall annually give 4 Shillings in Frankfurt currency for each Mass read, to encourage devotion, so that these services may be celebrated more laudably, reverently, and at the due time.

According to annual convent and monastic custom, the convent shall also celebrate a Mass in the choir in commemoration of Mary86 on the Feast of her Nativity.87 On the Sunday before or after, a splendid and solemn Mass shall be sung in memory of St. Mark and of Mary. To ensure that it may be all the more honorable, praiseworthy, and magnificent with all that befits a great feast, the captain shall provide 8 Shillings for each such sung Mass.

Likewise, as mentioned at the outset, the captain shall pay the sacristan 4 English88 annual wage for lighting the candles, preparing the brotherhood’s grave, and further tasks not otherwise entrusted to him.”

- See later in this article for a detailed deduction of this timeframe. ↩︎

- Bücher (1886): “Die Bevölkerung in Frankfurt am Main im XIV. und XV. Jahrhundert, social-statistische Studien.” ↩︎

- Monnet (1999): “German Historical Institute London Bulletin, vol. 21, nr. 2,” p. 53. ↩︎

- The cryptic name derives from the archival signature which in turn is based on the shelf number it is stored at. ↩︎

- For people less familiar with (Early Modern) German, Martin Fabian recently provided an accessible English translation in his book “Hans Medel’s Fencing.” ↩︎

- Apparently, this close neighborhood angered the monks: They demanded the windows of the Jewish houses toward the monastery to be bricked up. I found out about this exploring the (excellent) Museum Judengasse Frankfurt, where it was written on a plaque next to a window facing the monastery. If you have the chance, I warmly recommend a visit. ↩︎

- Weizsäcker (1923), p. 10. ↩︎

- My partial translation of these regulations can be found in the appendix. ↩︎

- While the grave is mentioned in the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations, it apparently vanished by the early 17th century, as it doesn’t appear in an inventory of the monastery’s graves anymore. However, we can infer its location based on the graves of similar brotherhoods – the locksmiths and bakers had theirs in the cloister, while the marksmen of St. Sebastian had theirs in the church. See Weizsäcker (1923), p. 106, 133. ↩︎

- Cod.I.6.2º.5, fol. 7v. ↩︎

- In this period, 1 Shilling corresponds to 9 Hellers in Frankfurt (Schneider, 2010), meaning a sung mass cost 72 Hellers. A carpenter was entitled to around 4 Hellers daily wage in 1450 according to Spies (2008): “Löhne und Preise von 1300 bis 2000.” This leaves us with a sum of 18 daily wages for a common craftsman. We can assume quadruple or quintuple wage for artisans like furriers or smiths, still leaving us with 4 to 5 daily wages. ↩︎

- Fischer (2022) : “Jacquin, Franciscus” In: Frankfurter Personenlexikon. ↩︎

- Powitz (1968): “Die Handschriften des Dominikanerklosters,” p. XXVII. ↩︎

- Koch (1892): “Das Dominikanerkloster,” p. 63 f. ↩︎

- Jacquin (c. 1740): “Succinctum Chronicon Conventus Francofurtani Ordinis Praedicatorum,” p. 168 ff. in ISG FFM, H13.14, Nr. 16. ↩︎

- “vor die schirmeyster, die in Sant Marcus bruderschaft sÿnt” (Jacquin, p. 172). ↩︎

- E.g., on Wiktenauer. The date given there probably refers to the complete original of the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations Wassmansdorff introduces in 1877 – and which has since been lost to time. ↩︎

- I am grateful to Michael Matthäus of ISG Frankfurt for kindly confirming the image rights of both entries in the citizens’ register and seals featured in this article. ↩︎

- Original: “peter von wissenkirchen gemeiner leut son ist bureg wored unt hat sich mit den Beckenmeistern vertragen umb die vii bb viii ß zubezalen arrod[atum] in die sti Joh decollatoni anno xiv lxxv” It was hard to find this entry as the register referred to fol. 121 b. However, fol. 116–139 have been moved after fol. 188. I therefore cite the more orderly printed page numbering. ↩︎

- See the transcription on Jens-Peter Kleinau’s blog “Vatternstreich,” created anonymously and edited by Daniel Burger. Werner Ueberschär, also listed as an author, kindly clarified that he initiated the transcription, but did not take part in it. ↩︎

- Kleinau (2011): “1488 Peter Weißkirch Captain of the Marxbrüder.” ↩︎

- I found his seal attached to a convolute of letters of employment from the late 15th century. (ISG FFM H.02.26, Nr. 1408). The same seal, but in worse condition, is attached to a 1490 oath of truce (H.06.09, 1821). Further letters of employment can be found under H.02.26, 1409 and H.02.26, 1410. ↩︎

- Cod.I.6.2º.5, fol. 9v f. ↩︎

- Kleinau (2011): “1488 Peter Weißkirch Captain of the Marxbrüder.” ↩︎

- Schulz (2015), p. 1. Although the church was destroyed almost entirely in World War II, this choir remains largely intact and can still be visited. ↩︎

- Reiffenstein (1871): “Reiffenstein-Manuskript,” Dominikanerkirche, Band 7, Seite 80, 8. Juni 1871. Edited by Historisches Museum Frankfurt. ↩︎

- Powitz (1968): “Die Handschriften des Dominikanerklosters und des Leonhardstifts in Frankfurt am Main,” p. XVI. ↩︎

- Weizsäcker (1923): “Die Kunstschätze des ehemaligen Dominikanerklosters in Frankfurt a. M.,” p. 132. ↩︎

- Given the incompleteness of the sketch, it is hard to say with certainty, but this could also be a bear. ↩︎

- Städel Museum: “Hans Holbein the Elder. Exterior Wings of the Frankfurt Dominican Altarpiece, 1501.” ↩︎

- Städel Museum ↩︎

- A reconstruction of the inner view by Dürer can be seen in the Historic Museum Frankfurt, and the outer view with Grünewald’s contributions is in the Städel. ↩︎

- To not misrepresent the Hellers: they were in fact among the few newcomers admitted into the patrician elite through trade, a case of upward mobility mostly limited to higher-ranking merchants and artisans. However, their departure from patrician society after 1502 only reinforces the point above. ↩︎

- Bücher (1886), p. 87. ↩︎

- I am grateful to Elisa Gianni for her valuable advice on word choice in the section heading. ↩︎

- Hils, Hans-Peter (1985): “Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes,” p. 175. ↩︎

- The reference to the lost Frankfurt regulations and to Wassmansdorff reached me via an article on Sprechfenster Blog (drawing on a suggestion from Eric Burkart to its author), which in turn led me via Jaquet (2010) to Hils (1985) and Wassmansdorff (1877), p. 139. I am grateful to Eric Burkart, who kindly confirmed both the fire and the Wassmansdorff source in conversation. ↩︎

- For more on Talhoffer’s life and his older coats of arms, I recommend this 2020 article by Paul Becker. ↩︎

- Burkart (2014): “Die Aufzeichnung des Nicht-Sagbaren. Annäherung an die kommunikative Funktion der Bilder in den Fechtbüchern des Hans Talhofer“. ↩︎

- Marxbruder Peter Falkner (captain 1502–1506) shows a similar St. Mark lion in his 1495 fencing treatise, MS KK5012, fol. 57v. ↩︎

- I am indebted to Sabine Kindel for directing me to the Marxbrüder seals, and for sharing her observations on the remaining Frankfurt holdings (ISG FFM, H.18.02 and H.18.03). The subsequent interpretation of the seal’s connection to the early brotherhood and Talhoffer is my own. ↩︎

- Upon sharing a draft of this article with him, Eric Burkart confirmed that the had made the same finding independently, and wrote about it in his recently submitted habilitation thesis. I am grateful to him for the exchange and his passion for the topic. ↩︎

- This conclusion rests on two points: (1) the late medieval typography, and (2) the presence of a second seal on the letter bearing the arms granted in 1541, which must therefore postdate the one discussed here. ↩︎

- Wassmansdorff (1877), p. 139. ↩︎

- The parchment is cut at the top of fol. 12v, immediately noting Persickh’s election but without a year. Based on Anthony Resch’s captaincy in 1522 and the usual biennial cadence, Persickh’s election can be inferred for 1524. This fits the reconstructed sequence of events presented below. ↩︎

- Proverb from the “German Peasants’ War” (1524–25) in my translation. I want to thank Tobias Prüwer who pointed me to this in January 2025 via his inspiring lecture and book on the topic: “1525: Thomas Müntzer und die Revolution des gemeinen Mannes”. ↩︎

- I am grateful to Michael Matthäus of the ISG Frankfurt for his insightful talk on the Frankfurt uprising, delivered during the 500-year jubilee in April 2025. His perspectives helped shape parts of this reconstruction. ↩︎

- No name registers of the participants in the Easter Monday agitation seem to survive. Laux Braun’s later prominence among the radical wing of the Frankfurt guild uprising makes his presence at the Peter’s Churchyard gathering likely, though not certain. ↩︎

- I would warmly like to thank Beate Dannhorn, registrar at the Historisches Museum Frankfurt, for kindly clarifying the image rights and licensing of this piece. ↩︎

- Except otherwise noted, the below account up to Easter Monday follows Hock (2001): “Reformation in der Reichsstadt. Wie Frankfurt am Main evangelisch wurde,” p. 3 f. ↩︎

- Schmidt (2022): “Vor 500 Jahren: die erste evangelische Predigt in Frankfurt,” p. 8 ff. ↩︎

- Weizsäcker (1923), p. 30. ↩︎

- Weizsäcker (1923), p. 30. ↩︎

- Kracauer (1875): “Geschichte der Juden in Frankfurt a. M. (1150 –1824),” p. 287. ↩︎

- Steitz (1875): “Das Aufruhrbuch der ehemaligen Reichsstadt Frankfurt Main vom Jahre 1525,” p. 1. ↩︎

- Frankfurter Verein für Geschichte und Landeskunde (1839): “Archiv für Frankfurts Geschichte und Kunst“ v. 12–13, p. 72. ↩︎

- Jung (1888): “Frankfurter Chroniken und annalistische Aufzeichnungen der Reformationszeit,” p. 177. ↩︎

- Bücher (1886), p. 87. ↩︎

- Schmidt-Funke (2012), p. 2. ↩︎

- Original: “Lucas Bryn Kursener eins Burgers sons Iuravit den Burger eidt feria quinta post oculi anno xv c xviii” It took me a while to decipher the date, which literally translates to “Thursday after Oculi,” i.e., the Thursday after the 3rd Sunday of lent. I recognized this liturgic day in context with surrounding entries marked “die mathy” and “misericordia.” ↩︎

- Cod.I.6.2º.5, fol. 12r f. ↩︎

- Talaga (2025): “Who Were the Freifechter? Let’s clarify the number and hierarchy of swordfighting confraternities in late-medieval Germany.” ↩︎

- Jung (1888): “Frankfurter Chroniken und annalistische Aufzeichnungen der Reformationszeit. Nebst einer Darst. der Frankfurter Belagerung von 1552,” p. 183. ↩︎

- The following up to “Frankfurt at the Heart of Revolution“ follows the account in Frankfurter Verein für Geschichte und Landeskunde (1839): “Archiv für Frankfurts Geschichte und Kunst v. 12–13,” p. 85 f. ↩︎

- It also is slightly misleading to call it “German,” as it wasn’t contained to today’s Germany. Instead, it also spanned Alsace, Switzerland, and Austria. Therefore, more recent scholarship often uses the term “Revolution of Common Men” – which in turn could be rephrased to “Revolution of Commoners.” ↩︎

- Blickle (1981): “The Revolution of 1525: the German Peasants’ War from a new perspective”, p. xx. ↩︎

- Frankfurter Verein für Geschichte und Landeskunde (1839): p. 86 f. ↩︎

- Kriegk (1862): “Frankfurter Bürgerzwiste und Zustände im Mittelalter“, p. 177 f. ↩︎

- Kriegk (1862), p. 178. ↩︎

- Hock (2001), p. 4. ↩︎

- Zade: “Die Frankfurter Zunftunruhen von 1525.” ↩︎

- Cod.I.6.2º.5, fol. 12r–12v. ↩︎

- Book (2007), “Die Chronik Eisenberger”, p. 356. Michael Matthäus was instrumental in discovering and transcribing the underlying source, available under ISG FFM, H.02.01, Nr. 96, fol. 62 r. ↩︎

- The inventory list does not seem to survive, and the Frankfurt Fencing Regulations only note “liturgical vestments and all that goes with them” (fol. 12v). Likely contents can be inferred from other confraternities with existing records, e.g., St. Sebastian’s Brotherhood (Weizsäcker 1923, p. 107). Earlier entries in the Regulations mention a black garment adorned with gold and silver in 1504 , as well as a shield and a silver chain in 1498 (fol. 10v) which may still have been among the properties. ↩︎

- Weizsäcker (1923), p. 21, footnote 9. ↩︎

- Afterwards, the guild is just called “Brotherhood of St. Mark” or “Masters of the Sword” (e.g., in the 1541 armorial grant), or later in their 1670 armorial augmentation “Masters of the Long Sword and Skilled Practitioners in Military Exercises of St. Mark and Löwenberg” (RHR Grat Feud Conf. 48-3-1). ↩︎

- Cod.I.6.2º.5, fol. 13r. ↩︎

- https://kdih.badw.de/datenbank/handschrift/38/1/1 ↩︎

- http://www.pragmatische-schriftlichkeit.de/Cod.I.6.20.5.html ↩︎

- https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bvb:384-uba002007-6 ↩︎

- Original: “alter herkomen,” a late medieval legal term translating roughly to “customary law” and implying that these customs are several decades old. ↩︎

- Quarterly fast days after St. Lucy, Ash Wednesday, Pentecost, and the Exaltation of the Cross. ↩︎

- Nighttime prayer on the eve of a church fest. With psalms, readings, and subsequent Eucharistic celebration. ↩︎

- Original: “Kloster der Prediger“ (“Monastery of Preachers”). Prior to World War II, the adjoining street was likewise called “Predigerstraße” (“Preacher Street”). ↩︎

- A reduced form of Mass without music. ↩︎

- Original: “ein meß im Cor von vnser lieben Frawen“ which could also mean “a mass in the choir of Mary,” as she was the patron of the high altar and church. ↩︎

- 8 September – around the time of the trade fair, for which the craftsmen came to Frankfurt. ↩︎

- Special currency, worth a bit less than Shillings. 1 Shilling = 9 Hellers, 1 English = 7 Hellers. Bothe (1906) “Die Entwickelung der direkten Besteuerung in der Reichsstadt Frankfurt bis zur Revolution 1612–1614,“ pp. 3–11.; cited according to Schneider (2010): “Turnosen, Englische und Heller.“ ↩︎

Leave a Reply